"God is fire in the head"

Nijinsky's Diaries | the Greek Magical Papyri | Carlyle's Sartor Resartus | Spare's Earth Inferno

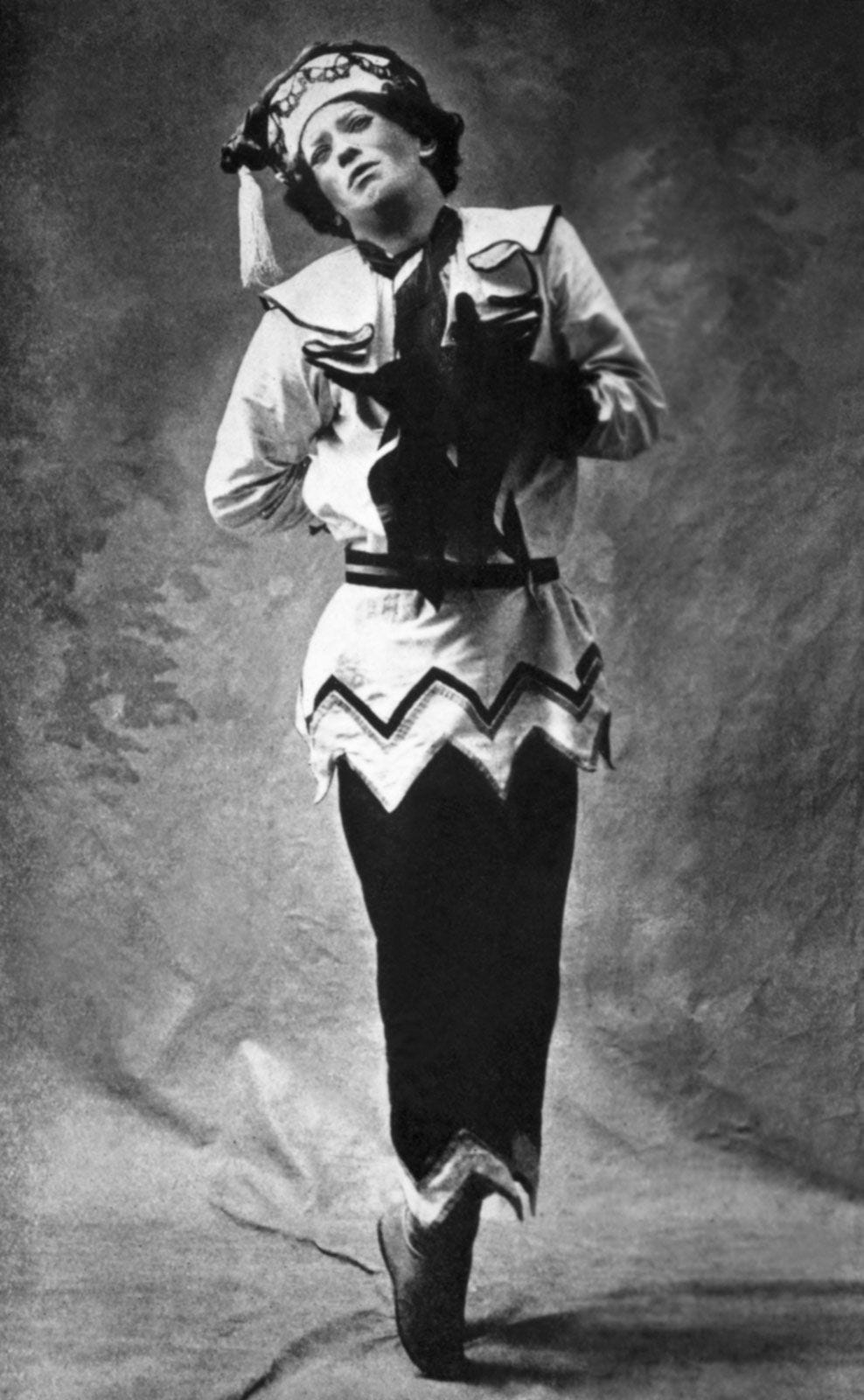

I’ve been reading Vaslav Nijinsky’s unexpurgated diaries, an unforgettable record of genius descending into psychosis. Nijinsky, the best male dancer of his generation and a groundbreaking Modernist choreographer, had an eccentric but powerful talent for expressing his outrageous personality through dramatic action. On the same day that he began his diaries, he gave his last public performance ever, to about 200 people he’d personally invited. The notorious master of modernist dance opened this last show by sitting on a chair and staring at the audience for about half an hour. Finally he stood up, laid two lengths of velvet, one white and one black, so as to form a cross, said, “I will now dance for you the war… which you did not prevent,” and began to throw himself violently around the velvet cross.

This was January 1919. In March he would be committed to a mental asylum permanently, but in the months between he wrote two diaries, “Life” and “Death,” filling their pages with short declarative sentences, one following hard after the other, in a breathless and jumpy free association that devolved into raving, childish fretting, and nonsense sound poetry, moving from proclamations like “Switzerland is sick because it is full of mountains” to “God is fire in the head” to “Je suis [Jesus]” repeated in compulsive permutations of ripped-up syllables. At times he wrote with a rhythmic, rather dancerly flair, like a ballerino with a sword of words; at other points he driveled about beans and politicians and the amazing pen he supposedly invented; sometimes, freed of all inhibitions, he was vicious-minded and even briefly imagined raping his infant daughter—but these thoughts were obviously intrusive, like all his thoughts, and mostly he exuded sweetness, vulnerability, compassion, and deranged love. He schemed to save the world, even as he was plunging headfirst into the abyss that he’d never leave again, ending up so addled he couldn’t even tie his own shoes.

Some of his stories of insane, God-inspired wanderings are especially memorable as tense minimalist narratives, with a flow and logic that reminds me of the Chinese writer Can Xue. But what I liked most was his hurt, flouncy, en pointe emotionalism, his artist-madman’s way of slicing through tripe. Here he is talking about the impresario Diaghilev, who extracted a sexual relationship from the much younger Nijinsky in return for boosting his career:

Diaghilev realized my value and was therefore afraid that I might leave him, because I wanted to leave even then, when I was twenty years old. I was afraid of life. I did not know that I was God. I wept and wept. I did not know what to do. I was afraid of life. I knew that my mother too was afraid of life, and she transmitted this fear to me. I did not want to agree. Diaghilev sat on my bed and insisted. He inspired me with fear. I was frightened and agreed. I sobbed and sobbed because I understood death.

Or here's Nijinsky being more truthful than any artist I’ve met:

I know what criticism is. Criticism is death. … I will say that a critic is selfish, because he writes about his own opinion and not about the public’s opinion. Applause is not opinion. Applause is a feeling of love for the artist. I like applause. I realize the value of applause.

And here he’s trying his best to help us all:

I feel that the Earth is suffocating, and therefore I ask everyone to abandon factories and obey me. I know what is needed for the salvation of the earth. I know how to light a stove and will therefore be able to light up the earth.

I can’t say I know much about Nijinsky’s career as a dancer. He first came to my attention through Frank Bidart’s poem, “The War of Vaslav Nijinsky,” written in 1983, a flamboyant and hyperarticulate piece of free verse with a rhythmic intercalation of styles and narratives, where enjambed lines step from side to side, dancing down the pages, and entire phrases or sentences appear in capitals for manic emphasis:

Nietzsche was insane. He knew

we killed God.

… This is the end of the story:

though He was dead, God was clever

and strong. God struck back,—

AND KILLED US.But I liked the poem more before I read Nijinsky’s diaries. For one thing, the dancer’s staccato style, with short sharp clauses one after another, is more unusual, fiery and effective than Bidart’s calculated and balanced eloquence. And the costume of madness Bidart tailors is too influenced by other cultural representations of insanity.

A poet can have his own style; that’s fair. What taints the poem more, for me, is that Bidart relied too heavily on a naïve anti-psychiatric interpretation of Nijinsky, structuring the dancer’s descent into madness as an intelligible character arc driven by guilt, guilt, guilt, hammering that one point as if the only thing that makes a man mad is trauma and sexual abuse and a society that mistreats him. In part, Bidart may have had this perspective because he’d read only the bowdlerized diaries released by Nijinsky’s wife, a rearranged abridgement which obscures the relentless galloping onrush of the schizophrenia. But the poet was also obviously reflecting the tenor of the times and perhaps his own preoccupations as a gay artist facing down a society that tormented him in no small part by making him feel guilty.

On the other hand, Colin Wilson’s The Outsider stakes out a similar interpretation of Nijinsky, locating the madness’s engine in Nijinsky’s lack of self-understanding. And I can’t rule out that possibility either, since I do believe that psychological and societal pressures contribute heavily to psychosis.

I will say that my ex-wife, a magnetic artist and Nijinskyesque figure in her own obscure orbit, suffered from recurring bouts of madness that I witnessed up close, and my impression is that madness is not just the content of what you believe (most sane people subscribe to at least a few insane beliefs) or the result of psychological pressure (many people stay sane through total emotional breakdowns) but also something happening deep in the brain on a level far below the consciousness. It’s not that your thoughts and emotions drive you mad, it’s that they whip and are whipped into a spinning fury by some cryptic neurological process that either doesn’t exist in most people or at least lies dormant, some eldritch stretch of the genome possessed by virus spirits out of space and out of time, jabbering nonsense demons who rip up sentences for salad. But I’m no parapsychiatrist—only a garden-variety ultracrepidarian reading the books of the dead.

Speaking of the dead, I've also been reading Hans Dieter Betz’s edition of the Greek Magical Papyri, an anthology of various Graeco-Egyptian scrolls dating from the 100s BC to around 400 C.E., with diverse incantations and evocations and other instructions for contacting the gods. Taken as individual works, these scrolls soon get boring and repetitious, almost always featuring a shopping list of magical ingredients (e.g., ibis feather, myrrh, a copper nail from a shipwreck) and formulaic syllables (e.g., EI IEOU ANCHEREPHRENEPSOUPHIRINGCH) to gibber on the third day of the month of Thoth, or whatever—but put the scrolls side by side, and you get an implicit panorama of timeless human problems. Our needs never change, but only our ways of fighting for them. And I really mean that our needs do not change at all.

There is, for instance, a spell for dealing with an angry boss. Or if you’re your own boss, there are multiple spells to help you succeed in business. And if you get rich enough to live on meat, then there are spells for removing a bone from your throat, alongside the spells against stings, dog bites, headaches, and hangovers. There is a spell to get an old lady as a servant, and also a spell to prevent a skull from gibbering horrifying prophesies—a nuisance that I suffer from nearly constantly.

But most common are the spells to make others like you, love you, lay you. One papyrus even specifies that the desired lover should forsake her husband and children. Kind of tellingly, there’s a spell to make a wife “love her husband.” For wives who do actively love their husbands, there are spells against periods, including one where lead is administered on the tip of the mage’s penis. In other spells that lowly staff, when smeared with the foam of a stallion’s mouth or the dung of a hawk, weasel, or hyena, can make any woman fall irresistibly in love with its owner. And for later, there’s a pregnancy test where the woman pees on a plant: if it’s scorched by morning, she’s still unseeded; if it’s green she will conceive.

Yet not only men were magi. There are love spells from lonely lesbians.

There are several spells to make friends, which I found touching—I guess millennial problems are perennial problems. I picture a naked magus slaughtering a white cock and walking backward out of the Nile clutching his talisman, in the hopes of summoning another dude into magic rituals and the deep cuts of Osiris lore…

Sympathetic, maybe, but other spells are crueler. Of course, there is a teeming diversity of curses. One papyrus includes a name you can whisper into a bird’s ear to make it drop dead. Another reveals how with one simple trick you can make a snake split in two. More troublingly, there’s a fragment that seems to involve cannibalism as part of erotic magic… maybe it’s a metaphor, but impossible to tell. For another spell you drown a cat while chanting formulae to trick the cat-god into thinking that actually your enemies drowned the cat, a hex all the more sadistic because its purpose is usually to stymie competitors in a chariot race. These antique magicians could be truly nasty and cunningly underhanded—as in the spell where you’re supposed to fib to the gods that your target insulted them in the grossest possible way, and so they should teach him a lesson, and pronto, please.

More in my wheelhouse is the so-called Homer Oracle. Apparently the veneration of Homer grew so great in antiquity that some practitioners attached mystical powers to his poems, snatches of which appear in many scrolls, some even meant to be inscribed on amulets. The Homer Oracle features 216 lines from the Iliad and the Odyssey; you throw three knucklebone dice, then draw out the matching line and apply it to your life, presumably by rooting deep in its signifiers for some kind of contextual similarity. This grab-bag of suggestive symbols is all too familiar, of course, it’s the type of mental technology that includes Astrology, Tarot, the I Ching, palmistry, the flight of eagles, scratches on ox bones, and much more. In such cases, there’s something deeper going on, I think, than just charlatanism or the useful tricks of cultural magic that let lowly oracles impose their political advice on heaven-mandated rulers. These technologies of consciousness work by playing on our elemental intellectual faculty of finding likeness, which itself is a basic component of how we assemble knowledge. Our power of creating meaning seems to originate, obscurely, in a kind of limited alphabet of feelings or ideations, a small number of possible configurations that interact to produce more complex notions.

Tarot, for exsample works on the willing user because we can find analogous patterns in just about everything—except we aren't likely to do so on our own, we run the same old thought ruts, and forcing the Tarot symbol to make sense compels us to go deep down into our meaning-making apparatus and wrench it onto a different route of interpretation then we’ve been applying to the problem so far.

I'm sure there's good scholarship on this, I'm just ruminating on my own, out of my nose, and probably all this is just the intro to the 101 of Pareidolia Studies.

I’ll write a little more about the scrolls once I’ve finished reading them.

This week I've also been inching through Carlyle's Sartor Resartus. I’ll talk about it more next time. For now I'll say only that it lies somewhere between Sterne, Swift, Nietzsche, and Friedrich. It'sannoying and amazing simultaneously, sometimes in the same sentence. One of my upcoming books has an intro that establishes its narrator as a sly metafictional trickster, with a permanent layer of irony between him and the reader, him and the story; this intro is so irritating that I had to cap it at 2,000 words. But Carlyle did that trick for like sixty pages! The whole time I had my jaw open, either astonished or asleep. But often astonished. One of the most eccentric books I've ever read, and it's great—but also I'm glad most people aren't like this.

Oh yeah, and I've been savoring Austin Osman Spare's Earth Inferno, published when he was eighteen. It's mostly drawings, only 31 pages long, and available online for free. As Alan Moore said, Spare draws like a single ravel of smoke unraveling across the page; think if Aubrey Beardsley had been a magician so deep into the occult that he pioneered his own branch of it, pairing weird, carnal, gorgeous images with oneiric declarations and more than a hint of hellfire—Spare’s anger and contempt being important ingredients in his work. He’s got this other text, Anathema of Zos, where he rants like an Old Testament prophet possessed by Milton’s Satan with Cioran on his night-stand and Black Sabbath on the victrola… he would’ve fit right into Colin Wilson’s book on outsiders, but at that point Spare had lapsed into obscurity. I’ll read more and report back in some later edition of A Book is a Deck of Windows.