Son of Eros

Spare's Anathema of Zos | Achad's 31 Hymns to the Star Goddess | Anaximander's wheels of fire | Orphism and the Orphic Hymns

Whosoever would be with me is neither much of me nor of himself enough.

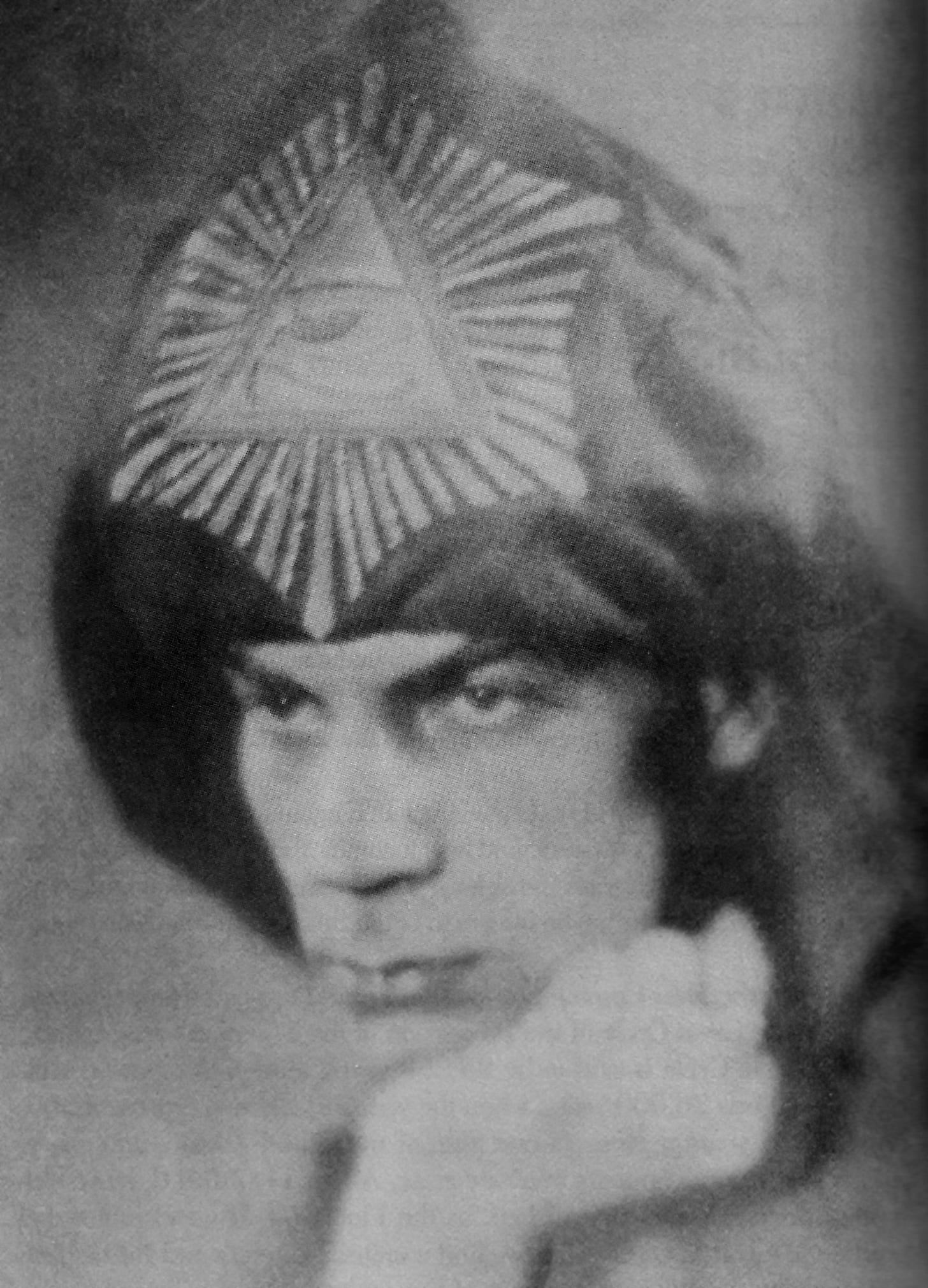

Last week I read Austin Osman Spare’s booklet Anathema of Zos / The Sermon to the Hypocrites / An Automatic Writing. Born in 1886, Spare won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art and made his reputation before he ever turned eighteen. The early days must have been good: he dressed with libertine flamboyance, was friends with Sylvia Pankhurst, and produced a series of eccentric and virtuosic drawings that looked like opium-smoky, infernalized Beardsley, Schwabe, or Ricketts.

But his notoriety soon dropped away, and he lapsed into an obscurity that lasted for most of his life. Nevertheless he wrote, painted, and drew prolifically, and got heavily into homebrewed occultism. After his death, his work and especially his magical sigils would inspire the occult movement known as Chaos Magic, of which I know zip; I’m just here for the art and the artist. Spare’s diableries had style.

Anathema of Zos appeared when Spare was 39. He had weathered the first World War, a divorce, and pretty much universal rejection, and the idiosyncratic bohemian prodigy had developed a sour but sonorous voice:

To cast aside, not save, I come. Inexorably towards myself; to smash the law, to make havoc of the charlatans, the quacks, the swankers and brawling salvationists with their word-tawdry phantasmagoria; to disillusion and awaken every fear of your natural, rapacious selves.

Like an Old Testament alt-prophet, or a fin-de-siècle Satan by Milton, or an artsy, hornier Nietzsche, in Zos he strides around purplefaced calling down hellfire on the bemazed masses, praising sexual freedom and maledicting the normies for quashing their natural desires:

Unworthy of a soul-your metamorphosis is laborious of morbid rebirth to give habitance to the shabby sentiments, the ugly familiarities, the calligraphic pandemonium-a world of abundance acquired of greed. Thus are ye outcasts! Ye habitate dung-heaps; your glorious palaces are hospitals set amid cemeteries. Ye breathe gay-heartedly within this cesspit? Ye obtain of half-desires, bent persuasions, of threats, of promises made hideous by vituperatious righteousness! Can you realize of Heaven when it exists WITHOUT?'

If you know the band Coil (they used that line about glorious palaces in their song Copacaballa), Osman Spare influenced their frontman, John Balance, who used to stomp the stage crooning threats and rituals, invoking strange extraplanar entities that Balance believed in with every ounce of his drug-tinctured multicolor-brain-tissue. And sure, Coil’s lyrics and Spare's writing are sometimes hyperventilated and wincingly pretentious—but I, for one, enjoy high-grade pretension, and anyway these self-styled sorcerers were often mostly not wrong.

MAN HAS WILLED MAN!

Spare’s folly consisted only of raising himself above others so very highly, yet without doing so he could never have made so much self-willed, stubborn art in the face of critical disapproval. His work would never have lived to be revived. As the lonely last Decadent, sputtering blasphemy like a quiff-headed priest of the black sabbath, here he comes off as a ridiculous, ranting, spittle-spraying scarecrow Jeremiah, albeit with drawings as awesome as unraveled moonlight, as the damned twisting out of the earth; he opens by insulting and caricaturing even those who read and heed him; he hates us all; I like him very much. I miss sneering elitism, I can’t stand this populist sunshine everybody-wins bullshit. Bring back contempt!

...is what I would say one moment. The next moment, considering Spare himself, I'd give way to a generous, open-hearted acceptance of messy individuality and untenable conceit—a forgiveness I extended as well to the next booklet I read, Frater Achad's 31 HYMNS TO THE STAR GODDESS Who is Not, subtitled BY XIII: which is ACHAD. Though Achad is also an early 20th-century magician, his tone is entirely different. Spare—ragged, bedraggled, and almost certainly unshaven—stands with a giant erection on a dias of burning trash and summons meteorites down upon the filthy ruck, whereas Achad adopts a gentler, more elevated and poetic position: turning his back on the writhing wormlike masses, not even acknowledging them, he lilts a burgundy encomium to the cosmos. I’ve been both of these men in different parts of my life, sometimes in a single day, a single conversation.

Frater Achad began his adult life as an accountant called Charles Stansfield Jones, but eventually he rose high within several esoteric fraternities. That’s why I love magic: it allows an ambitious accountant to do things like earn the “high-ranking IX°” in a cryptic magical consortium by proving knowledge “of the Supreme Secret of the Sovereign Sanctuary of the Gnosis.” He was able to put on fanciful hats and stare broodingly at the astral plane. He could take part in acronymic organizations whose members wrote to each other using envelopes in envelopes, purple typewriter ribbons, and custom paperclips. He could write a book called Crystal Vision Through Crystal Gazing, in which he suggested that we turn regular glass into crystal within our own “Inner Being.” He could consider himself Past Grand Master of the United States of America right up until he caught a cold waiting for the bus and died of pneumonia three days later. Magic is a mighty equalizer: any sultry wonk of szyzgies may ascend past kings to kiss a star-skinned goddess on her sidereal lips.

Well, at least as long as the ascendant in question is blessed by Aleister Crowley, who for a while considered Achad his "magical child" and "beloved son." 31 Hymns to the Star Goddess is built on ideas from Crowley’s Law of Liberty, where the Star Goddess is the Egyptian goddess Nuit, who represents the entire universe in the cosmology of Thelema (Crowley's magico-philosophical system). However, you don't need to know anything about Crowley to pick up on the most important ideas in the hymns.

T.S. Eliot it’s not, but I never read these wizards just for their texts—I always imagine them uttering the words as characters. Achad's voice rising like heavy incense, lugubrious even in ecstasy... His dense, dramatic eyebrows like severed segments of question marks. His foursquare nose. His hypersensual lips of a transcended beancounter. Robed and ringed, wreathed in acronyms and decked with archaicisms, he has arrayed himself to sing his love song to the universe, and at times he ascends into a solemn, sacred beauty, even if a whiff of cosplay lingers…

Neither Spare nor Achad could have written without Romanticism moldering in its grave behind them; they both worked against a cultural background where ordinary individuals could possess or earn a special enlightened soul of Genius. The ancients elevated the gods; we elevate ourselves even when we hide in modest beetleshells. Elevating ourselves was a great step forward, though it took us into an abyss our societies haven’t crossed yet—but, well, still, sometimes I find it hard to breathe in the same room as these Enlightened Geniuses. Maybe because they’re taking my implicit shtick. Or maybe because the aloof speculations of the ancients, their radical stories about the universe, led to acts of imagination that were more impersonal in their mythologizing and so all the more striking. Wistful for the pre-Socratics, I thought especially of Anaximander's cosmology as described in Philosophy Before Socrates:

The earth is at the still centre of the turning cosmos; about it lie concentric wheel-rims, one for the stars, one for the moon, one for the sun; the wheel-rims are hollow and filled with fire; and heavenly bodies are holes in those rims, through which shines the enclosed fire.

I don't always want a starry universe in the shape of a woman, with me as a supreme mote before her. Give me wheels of flame revolving in wheels of flame, flame in flame in flame rotating in my skull's vault of bone, lighting my little eyes into fireballs...

Still nostalgic for antiquity, I picked up the Orphic hymns in an edition translated, introduced, and annotated by by the mind-bogglingly knowledgeable team of Apostolos Athanassakis and Benjamin Wolkow. The hymns, much more self-erasing than the efforts of Spare or Achad, are gorgeous and strange, with many esoteric twists on mainstream Hellenism, and shot through with picturesque concepts of madness—Orphism was a cult of Dionysius, with plenty of wine and insanity. Yet the hymns are gentle and devotional, dignified and graceful, and if their lyrics are any indication, the cultists ultimately sought release through madness:

The Bacchantes escort

the holy Lenaian procession

in sacred litanies

revealing torch-lit rites,

shouting, thyrsos-loving,

finding calm in the revels.Though attributed to Orpheus, the hymns were probably composed by someone in Asia Minor between 100 and 500 C.E., for Mystery rites we know little about. There are 87 hymns in total, all of them alike. Each hymn is dedicated to a single god, with an invocation, a flattering description of the deity, and a request for aid, protection or purification. Athanassakis and Wolkow suggest that the hymns were chanted at eventide in sacred places with candles and incense, the believers caroling hymn after hymn in a marathon of praise, in a sequence that went from birth to death, from the primordial gods to the pantheon to the chthonic. Imagine choral voices wafting up through sibilant leaves to the Mediterranean heavens:

To Pan incense--et varia I call upon Pan, the pastoral god, I call upon the universe, upon the sky, the sea, and the land, queen of all, I also call upon immortal fire; all these are Pan’s realm. Come, O blessed and frolicsome one, O restless companion of the Seasons! Goat-limbed, reveling, lover of frenzy, star-haunting, weaver of playful song, song of cosmic harmony, you induce fantasies of dread into the minds of mortals, you delight in gushing springs, surrounded by goatherds and oxherds, you dance with the nymphs, you sharp-eyed hunter, lover of Echo. Present in all growth, begetter of all, many-named divinity, light-bringing lord of the cosmos, fructifying Paian, cave-loving and wrathful, veritable Zeus with horns, the earth’s endless plain is supported by you, and the deep-flowing water of the weariless sea yields to you. Okeanos who girds the earth with his eddying stream gives way to you, and so does the air we breathe, the air that kindles all life, and above us the sublime eye of weightless fire; at your behest all these are kept wide apart. Your providence alters the natures of all, on the boundless earth you offer nourishment to mankind. Come, frenzy-loving, spirit-possessed, come to these sacred libations, come and bring my life to a good end. Send your madness, O Pan, to the ends of the earth.

The Orphic deities are both familiar and weird, twisted by the Mystery cults and melted by the syncretic heat of later antiquity. Make any doctrine secret, mysterious, and accessible only to the initiated, and in the cultic darkness it will ember into odder blossoms. Heracles, for example, becomes a Titan and solar deity. And Pan has been identified with Zeus—in fact, he’s morphed into fatherless, self-born, celestial Pan, whose body maps onto the universe. His horns, they’re the rays of the sun and the crescent of the moon. His ruddy complexion is the ether, his spotted fawn-skin the stars, his hirsute legs the forests of the earth, and his hooves its compacted soil. The randy satyr, sender of panic, has gone cosmic… In still other places he’s identified with Dionysius, who in turn is identified with Zeus and Protogonos, and some scholars have argued that these last three should be understood as aspects of a single triune Orphic deity (perhaps less Trinity than Trimurti). Mysticism melts all into one—muse on cosmology too long and the mind seems to tend to unify, to obliterate differences and reduce individuals to aspects, fusing separate gods into Cerberus heads.

But wait, who is Protogonos? He’s also called Eros, but don’t be fooled. Protogonos is the only specially Orphic deity, secret creator of the other gods, and—as you’d expect of the cryptic god of secretive cultists who staged amazing, boundary-breaking parties, unforgettable revels—he is weird. Really weird. God is a freak. Behind the cloudbound crew of familiar Olympians lurks a horrifying mutant.

In the Orphic theogonies described in The Orphic Hymns and on the Hellenic Gods website, at the beginning there is only indescribable, unknowable and imperishable oneness. Then Time, moved by Necessity, gives birth to Aether and Chaos, who produce a silver egg that whirls around in enormous, wondrous circles. When the egg breaks open, the upper half becomes Sky, the lower half becomes Earth, and, presumably within the cosmic goop clinging in magmatic strings to the broken halves, there appears a bizarre, two-bodied, male-and-female deity. In one version Protogonos/Eros has four golden wings, four horns and four heads: ram, lion, bull, and serpent. In another version he has bullheads growing from his sides, plus a snake head that looks like many different beasts. This blisteringly surreal hermaphroditic prog-rock deity builds an immortal pad for the gods and also makes the moon, which has lunar mansions, lunar cities, and lunar mountains. Though he shines brightly, he can be seen in full only by his daughter Nyx, Mother of Dreams. Perhaps to his daughter he looks beautiful.

I hope so, because he is not just her father—he’s her lover too, and soon her baby-daddy.

After that point, Protogonos/Eros, immortal inseminator of the anthropic cosmos, unfortunately fades out from the theogony we know, and the story resembles for a while the more familiar events from Hesiod. The god’s brat is Uranus, first victim of the delightful proto-Freudian father cycle of Uranus to Cronus to Zeus, where each son chops off his father's genitals. Uranus’ genitals plop into the ocean, and from their foam up pops Aphrodite, god of love. Later, in an absurd but appealingly silly image, Zeus rides a comely she-goat to Heaven (shades of Pan?). Later still, Zeus lays Demeter as usual, but oh no—in Orphism, Demeter and Zeus’ mother, Rhea, both fertility goddess, have been syncretically melded, meaning that Zeus, having castrated his father, has sex with his mother. Their child, Persephone, is Zeus’ daughter-sister; and soon, disguised as a snake, Zeus impregnates her as well, generating his son-grandson-nephew-brother, the wondrous Dionysius.

Now, finally, we’re treated to the Orphic salvation myth, which is barely alluded to in the hymns themselves. Dionysius, in his early form Zagreus, is Zeus’ favorite; the elder god even sits his bonny baby boy on the divine throne. Nettled and envious, the seven pairs of Titans paint their faces white and approach Zagreus in secret with a basket of seven toys, from which the baby hauls out a mirror, spellbound by his own image. The Titans grab at him; in desperation the baby metamorphoses through a myriad of animal forms, from male to female and back, yet he slowly succumbs, staring mesmerized at himself in the sparkling mirror. In the end the Titans pounce on Zagreus, rip the baby god to pieces and consume him in a great holy rite, but their festivity lasts only briefly before Zeus pops in and incinerates them with lightning. From the Titans’ ashes, charged by the god’s electricity, rises the human race. Thus our foul bodies, originating from the Titans, are evil, whereas our electric souls hail from the Aether of Zeus, which means we can be saved. Body bad, soul stellar: you know the drill. After a further rigmarole which includes Zeus sewing a fresh fetus of Zagreus into his thigh, the slain baby god returns as Dionysius, rides in a red basket to the abode of gods, and learns there the Orphic mystery rites. Having tasted death, Dionysius turns to helping us escape our passions and sufferings in this miserable prison world, in this Titanic Age, channeling the infinite mercy of the still uncastrated Zeus (fingers crossed). Through Dionysius we are saved.

Sound familiar? A god’s son dies and comes back, and his suffering paves the way for our salvation. It’s fun to imagine a syncretized, bicephalic Dionysius/Jesus, one face all drunkenness, laughter, madness; the other serene, loving, and lambish… On the other hand, I’d rather not merge the gods. Something was lost with the mystery cults, some ancient celebration of frenzy we should have kept as a release valve. I miss their fickle and overwhelming god of revels, their vinous dissolver of boundaries who, wagging his pinecone-tipped staff, granted the bacchants temporary freedom from the frustration and despair of trying to resist change and maintain control in their little, flylike lives. Athanassakis and Wolkow describe him best:

[Dionysos] is a god of vegetation, particularly of the creeping vine. He is a god of liquid fertility: the catalyst that initiates the process of growth, the vital force that sustains it, and the fluid nourishment that flows from it. Semen, blood, water, wine, honey, milk—Dionysos is all of this. His very essence is a fluidity that is at once defined and undefined. At his roots, he is a god of transitions, but in order for there to be a transition, there must be a point A and a point B between which a transition exists. Dionysos swings between these extremes. At any moment, the god can move from one to the next. He is a god of opposites: peaceful and warlike, human and animal, sober and drunk, alive and dead, sacred and profane.

A personality worth keeping around. All the same, I can’t help imagining a cross-pollinated Jesus, the Roman soldiers gathering as Judas presents him with a scintillating mirror. Hypnotized, Jesus stares at his own radiant, beautiful face, the clean face of a godson on the verge of apotheosis. Finally he sees what others see, and he can’t look away, and so he is killed, and so he returns, and so he is fed weekly to his worshippers, who, in the early years, drink his wineblood by moonlight. Somewhere far above them the invisible, shining creator God patrols on four golden wings, the bulls’ heads in his sides roaring across the universe, his snake head flickering through terrifying animal fantasias. Jesus, son of Eros. His blood dissolving in your veins, loosening your limits. Thrilling you to the touch of the universe.

I didn't have room to mention that the Chaldean oracles, from about 160 C.E., feature an entity called Eros in a perhaps not unrelated role. This Eros, subordinate to the ultimate creator, serves as the active binding principle of the cosmos. Ruth Majercik in her book The Chaldean Oracles: "The Oracles also mention Eros independently as the 'first' to 'leap' from the Paternal Intellect. As such, Eros functions as a cosmic principle whose 'binding' quality preserves a sense of harmony not only in the Universe but in the human soul as well. As such, Eros functions in much the same way as the Connectors, Iynges, and Intellectual Supports; in Geudtner's analysis, these last three are all 'held together' through the 'binding fire' of Eros as 'die ausführenden Organe des Eros.'"

i enjoy your voice, it's very present