I ~ The Great Invisible Spirit

You have a body, a soul, and a spirit. The body rots and the soul kills itself, but the spirit is particular, peculiar, special. The spirit is the yolk in your self’s egg. It is the reality amid this dream. It is your vivifying cosmic light, holy and normally immortal, and in fact it did not originate in your puny human self but was borrowed from God and trapped inside your body’s prison, your soul’s hole.

Yet your speck of divine light is not safe. If you don’t arrange its heavenly escape through gnosis—that is, through secret knowledge of spiritual mysteries—then when you die, you vanish forever, your sharp spark of holy spirit pulled down guttering into oblivion along with the material that cages you. From fullness to dust, from God to garbage; that’s what happens to us. As The Gospel of Philip says, “This world eats corpses, and everything eaten in this world also dies. But truth eats life, and no one nourished by truth will die.” So trust me: what you need is gnosis.

Well, and an extra baptism wouldn’t hurt. A baptism of fire, a baptism of light. You know. Just to be safe.

Or so an ancient Gnostic might have said to an unusually tolerant Christian, circa 300 CE. A few midnight meetings later, he might let slip that the Trinity is slightly more extended than popularly believed, or that our bodies are patterned on the Cosmic Man. I imagine his eyes flicking from side to side, before he unwraps a bundle of scrolls, pushing away The Archangelic Book of Moses the Prophet in favor of an insanely detailed diagram of the cosmic man labeled with the 365 angels of the solar year and their one-to-one correspondence to the parts of the human body. Incidentally, he says, did you know that there is a soul of hair, a soul of bone, a soul of skin? A psychical body that overlies our physical body? He’s been smiling, slowly putting down his inhibitions, for the Christian has been plying him with date wine, and anyway the Gnostic is just so relieved to have found a friend, a fellow traveler fascinated in secret knowledge, in true salvation, in escaping their hostile world…

Unfortunately, the brotherly-faced Christian has decided to denounce him first thing tomorrow, and his valuable scrolls will be destroyed, and before long the Gnostic senses the vibe drop and deteriorates to nearly whispering his best secrets, in a rush of implicit pleading. Adam was androgynous, you see. The Holy Spirit is the Triple Male. Material is evil. Material is the portion of corruption nailed to our spirits; like a satanic Jesus of darkness it suffers from our purity. We have been fettered with forgetfulness and deafened by death. Also: maybe not everyone has a spirit. Only some do; the others are just creations. And as for the fellow popularly called God, well he, uh… has a few dark secrets… “Oh, don’t look so uptight,” the Gnostic might say, chuckling anxiously. “Remember, I’m a Christian too!”

And he’d be right. Back in his day, the Roman Church hadn’t yet cornered power, clamped down on all other doctrines, and crushed the mindbending diversity of early Christianities in the Wild Wild Near-East. All around the Gnostic, there fumed and flowered a largely unpruned, rampant garden of sects and types and lifestyles, whose swarms of heaven-hunting believers spread out into hundreds of groups, used dozens of gospels, and disagreed on the most basic elements of doctrine, their beliefs resembling one another yet differing like the dialects of diverging spiritual languages. Within this ferment already shadowed by the upraised boot of the Church, the sects we refer to as the Gnostics—actually Sethians, Valentinians, Thomasites, Cainites, Ophites, Carpocratians, Borborites, and many others—were often little more than particularly spicy and cutting-edge Christians, a sort of semi-exclusive and avant-garde R&D tendency, their adepts intent on hidden knowledge, personal enlightenment, and the occasional rapturous ascent. Many believed in Jesuses, in an unfolded Trinity, in a higher baptism; it’s just that they also happened to mistrust the Abrahamic God and his world; to differ on the meaning and status of Jesus; to draw ideas from Platonists, Neopythagoreans, Zoroastrianism, loose myths, and possibly their dreams; and to ground salvation not in the problem of sin but on the pursuit of gnosis, their writers regularly soaring into metaphysical flights of rhetoric that portrayed our world as a cosmic mirage, an intoxicating nightmare from which the inspirited seeker must only awake.

Against these boutique mystics, the Church had every advantage. It had party loyalty, centralized discipline, and a soberer, somewhat more realist Christianity, with a message aimed at everyone and not just the self-selected few. It had simplicity, organization, and ruthlessness, grace and very sharp knives. The Church Fathers would put the Gnostics to great use, in part defining their own orthodoxy through the expulsion of Gnosticism and the execration of its texts… which is a shame, even just for art. So many eccentric, beautiful, and surprising ideas must have vanished forever into graves and fires! Before the Church’s iron gate whanged shut and the flames ignited, the Gnostics had been carting around wheelbarrowfuls of cryptic books, glittery kaleidoscopic treasuries of alt-scripture: cosmogonies, incantations, prophecies, apocalypses, some of which were masterpieces of mystical rhetoric, offered original answers to notorious theological conundrums, or upended mainstream Abrahamic stories and embroidered them with conceptual rhinestones.

Just flip through the fraction of texts that’ve survived—scriptures like The Tripartite Tractate, The Secret Book of John, The Holy Book of the Great Invisible Spirit, Eugnostos the Blessed, or The Gospel of Judas—and you’ll meet the female Holy Spirit, Judas as a double agent working for the side in white, the snake in Eden as a hero bringing the gift of enlightenment, and Jesus laughing on the cross because his real body, his spiritual body, is uncrucifiable. You’ll hear the cross itself speak. You’ll be treated to ritual glossolalia and cryptic hints at a baptism called the Five Seals. You’ll see the first trees sprout from angel semen. You’ll be serenaded by the howling mad oracular declaration of mystical female power called Thunder, Perfect Mind. You’ll read prayers for escape, visions of cosmic churches, of the abolition of illusion and the death of death. Of how Error, with power and in beauty, made a substitute for Truth. You will be told that humans ate of two trees, the Tree of Enlightened Insight, and the Tree of Life, which cursed our spirits to forget eternity: now we have been “bound with dimensions, times, and seasons, and fate is master of all.”

You’ll run across Sethians casting themselves as a kingless generation of world-rebels, seed of Adam’s third son, Seth, who donned the mask called Jesus in order to vanquish thirteen celestial entities called aeons. The Valentinians, on the other hand, imagined their earthly church as a mirror of an immortal church and held baptismal weddings in sacred bridal chambers, each spirit pairing with an equivalent angel. The soul got compared to a slut; the world to dirty sperm. In Thomasite sources, you’ll learn that Jesus sold his twin brother, Judas Didymus Thomas, into slavery to an Indian captain—but only so that Thomas would preach in India. In Patristic records, you’ll be told that the Cainites worshipped Cain, the Ophites worshipped the snake, the Carpocratians worshipped themselves, and as for the Borborites, well, you’re probably better off if you never find out what they supposedly worshipped. (In particular, you should never look up what Epiphanius said about The Greater Questions of Mary.)

But the most audacious and churchshaking of all Gnostic myths—the myths that brought the Church Fathers’ meteors down upon their heads, the myths which finally sent our hypothetical Christian shouting into the cold desert night, cursing our Gnostic to the Devil—are the shocking creation stories which claim that the Jews and Christians had all the details backward, upside-down, and darkly, that the Abrahamic God was not what naïve Abrahamites believed, that Genesis misled with malicious intent, and that the Question of Evil, that persistent puzzler and atheist-maker, had the simplest answer imaginable.

See, many Gnostics split the Abrahamic God in two.

They had an upper God of unmitigated goodness, the Great Invisible Spirit, the transcendent Middle-Platonic God, the God of Jesus and of Paul, you know him: he’s the ineffable, unknowable, taciturn and enigmatic Father of Justice, to be kneeled under with utmost humility. This omnipotent self-originator was the first maker and the source of all spirit, and he created through thought, forming ideas which solidified into autonomous beings. First he emanated the rest of the Trinity (at least in some texts), but then he branched like a cosmic river into a flowing family tree of divine attributes, emanations both separate and a part of him, plural and one, grooving interlocked in a higher-dimensional bliss of mutual adoration. In some versions, this perfect All-Father had no direct role in the creation of our world and bore absolutely no responsibility for our suffering; pain only appeared after the youngest emanation, called Wisdom, or Sophia, struck out alone and committed a catastrophic spiritual crime. The nature of her crime varies from to text, but usually she attempted to create by herself, without her obligatory partner, or to comprehend the upper God; either way, she violated the cosmic order, acting in presumption and deficiency, out of unspeakable pride; and from her pride was born a monster.

This was the lower God, an evil deity called Yaldabaoth or the Demiurge, a mid-powered craftsman-God adopted from Platonism but mutated by some Gnostics into an insecure and psychopathic loser. Born with the head of a lion and the body of a serpent, this hideous, repulsive, cackhanded cretin woke up alone in darkness, concluded that he had made himself, and then—since he was only a cracked mirror of the great invisible creator—set about slapping our unreal world together, making it from shadows and dreams and other spare images. As he worked, he unconsciously copied heavenly forms and hierarchies… and did a terrible job. He may have been evil, he might have created a million styles of suffering, but Yaldabaoth was not at all a Christian Satan, not some diabolically intelligent heavy-metal pain-lord looming over his earthly hellscape. No, this moody, jealous punisher, this embodied sacrifice-sniffer, this amateurish meddler roving up and down and flinging lightning bolts at his own creations, demanding ceaseless slaughter and sacrifice, was no one other than JHVH, the God of the Old Testament, revealed as a murderous jerk and a dumb, talentless hack, his mediocre world like a child’s drawing blotched with red scribbles of blood, a moldy, stinking parody of all goodness and worth.

Worse, Yaldabaoth suffered under his own inferiority and lashed out when he felt challenged. After humans threatened to surpass him by enlightened insight, he shackled us to fate and locked us into death, so that we would forget our greatness which made him feel so low. Imagine: billions of people have died in the mostly ghastly conceivable ways, all because our gnosis wounded his ego. A petty tyrant writ cosmically large, he would have been pathetic, even pitiable, if he weren’t the showrunner of our lives, the petulant orchestrator of all pain, bitchily yanking at the puppet strings of the theater of torture that we think of as our world. In his colossal junkyard of illusions we reel around confused by death, dazzled by materiality, blinded by the daily phantasmagoria of horrors, having abandoned our inner wells of living light—but all the same, our flesh-buried sparks of spirit are ever tantalized and lofted by the giddying fragrance of the All, and our darkened minds do always sense on some level that we do not belong here, that it is possible to wake up from this nightmare, that reality is not real, existence does not exist, and to be is not to be.

We must picture our early Christian, in the hypertense moments before his noisy flight, staring with nauseated horror at the Gnostic. That bloodhound of enlightenment hasn’t looked up in a while, retelling his creation story with fear and trembling, mesmerized and moved all over again by this heady doctrine which contains the solution to his suffering, the explanation for his pain, for his fears and feelings about the world, about being watched, toyed with, persecuted, about being misled and betrayed and hated, about truth being concealed and difficult to find, about the somnolence of the masses. The demonic pains in his gut, the death of his infant daughter, the idiots in charge everywhere at all times, the staggeringly high victory-rate of the forces of darkness, the godawful, unforgivable suffering of innocents—all this finally made sense. Our Gnostic found an elegant answer to the Question of Evil, and had the Churchites been able to bear it, they might have saved themselves millennia of defensive oratory on the perennially red-eyed and heart-rending question of why innocents suffer. Ask the Christian why a good God made evil, and you might get that familiar rigmarole about how we are granted free will in order to be tested, to sort good from evil and place our salvation in our own hands; ask a darkened luminary like Dostoevsky, if you want to be informed that we need to suffer to be able to choose Jesus, and if necessary the poor must starve and die. All those blameless children who get beaten, diddled, napalmed? They’re collateral damage in the great sorting of souls, victim of someone else’s wrong choice, destroyed by a design some call intelligent. But why, precisely, did a good God have to make evil? Why cancer, why brain parasites? Why boil us in the tar pit of time? The Gnostic shrugs sadly, expansively, with thick maroon smudges under his eyes, and, idly rotating a lamp he’s staring into, with little lights dancing in his pupils, reveals the truest thing he knows: that innocents bleed, the rapacious rule, and our lives are carnage incarnated, because our world is a psychotic prison made from pride and pain, a ceaseless cycle of suffering dreamed down by a colossal lion-headed wanker. Our world was created by a counterfeit, a ravener and a ravisher, a violent and childish moron, and we may confirm the bad news with another insight from the Gospel of Phillip:

GOD IS A MAN-EATER, AND SO HUMANS ARE SACRIFICED TO HIM

II ~ Silence-Pronoia-Barbelo

But the Church won. They defined their enemies, hereticized them and silenced their books, and did it with such meticulosity of erasure that the ecstatic Gnostic torch-parade soon fluttered down into a constellation of candles.

The official story runs like this, more or less: After the fourth century, the flames of Gnostic enlightenment slowly cindered out, baptismal waters sank into mud, spirits sputtered in phlegm. By the late Middle Ages, the very last tremulous sighs of Christian Gnosticism had wafted up to the heavy heavens, wisps of spiritual yearning escaping from the dusty lungs of peasants and outsiders as they crept through the oppressive shadows of vast, stained-glass-eyed factories of mass ideology. These rebellious believers, side-eying the corrupt and blathering ecclesiasts, probably had good reason to think that a malicious God had coughed up our world, and no doubt they were looking forward to the Kingdom of Heaven as much as anyone ever had—but all the same, the Church’s marble jaws rumbled wide and disgorged ranks of tier-hatted men marching with eyes piously lifted, brandishing gold-plated croziers and speaking in ropy streams of white words that twined from their mouths and spiraled out into scrolling curves of eloquence as clean and cold as new snow. If my memory of the history books serves me right, these incanting priest-soldiers were chanted onward by choir boys, escorted by six-winged seraph-heads and the occasional chariot with wheelspokes of light—and the birds brought them their breakfasts. You know these men from medieval paintings: lily-clutching eunuchs with gold halos, they dressed in uniform robes and garlanded themselves with porcelain rhetoric, presenting themselves as shepherds and lambs, if such creatures were organized in a hierarchy brooking no dissent from the party line. In some Renaissance portraits one begins to glimpse the dark scruff of their hard jaws, of their jowls of war. They won again, and again, and again, until finally Luther hammered his nail into their church-door foreheads.

But that tale is only almost true. Right under the butternut noses of those purple-lipped, flappy-eared men wearing dresses and drinking their god’s blood, there has thrived all along an opposed binary—a parallel counter-organization with its own trunk, roots, and branches, books and prophets, flourishing for more than two thousand years and indeed far stronger and more focused than ever, or so I’m told. Much smaller and discreet to a fault, this subterranean mirror-church, reflecting light from the true heaven, shimmers like quicksilver in the secret veins of our cities, shining from the windows of apparently normal homes, in the spiritually beautiful faces of shrewd and watchful women, each of whom keeps an eye on the salvation of the universe, nursing a tiny emerald flame of enlightenment even while great throngs of unawakened believers, exalting a toxic god, perish as material in the material world.

These brave women, working behind the scenes for our salvation, belong to a Gnostic church known as the Temple in the Wasteland, a rigorous sect helmed by a long line of matriarchs who have made an exquisite art of maneuvering around brutality. They give out no copies of their scriptures, accept most followers only after years of vetting their intentions, and meet just once a month after much solo study and exploration; a typical member lives with unwitting friends and family, and converts her children only if they show above-average intelligence and discretion.

Many an awakened woman has had to face that her own offspring are not worthy for spiritual ascent, and must die into the world, absorbed into the ravenous earth.

The Temple in the Wasteland are not kidding around. Undeviatingly vigilant for our salvation, they keep stubbornly driving themselves to the limits of their intelligence and beyond, churning out power rituals, ecstatic ascents, and visionary odysseys which have prevented innumerable astral disasters from ever occurring. Yet do they seek rewards material or social? Not at all! Instead of swanning in megachurches or peacocking in Rome, the Temple dwell in ascetic obscurity, maintaining their headquarters in an industrial zone outside Toronto, in an unobtrusive concrete bunker that does not look in the slightest as if it houses the international nexus of universal redemption. Peer through its front window and you’d see only a square of schooldesks and chalkboards, a few posters with unfamiliar sayings from Jesus, and a back door which, if unlocked, would lead you through windowless corridors to the camouflaged stairs down to their innermost sanctuaries.

But before you ever got that far, you’d run into the high priestess Norea—or rather you would suddenly be impaled by the brilliant double headlights of her eyes, which have a way of leaping forth from darkness like shining white swords. You’d probably cry out, sopping with sweat, feeling as if you’d done something terribly, soul-doomingly wrong, your worst self seen and judged. Even so, as soon as the cry left your throat you’d feel a little silly, for Norea is unsettlingly, almost abstractly old, wizened and rheumy-eyed and thick-bespectacled, with a ghostly crown of thin white curls. Every year has left a chisel-scrape in her skin, whittling her away to the center of the marble block of her body; now she’s all cartilaginous angles and hollow skin glued to the bone, sharp as a prehistoric stone shard. Probably this eerie vision of human acumination would stonewall you, her ocular brilliance would fade and she’d smile half-blind over her bifocals, hugging a stack of lexicons, and croak about her private study group for the translation of old texts, making it all sound boring and suffocatingly academic. If you could persuade her to let you stay, however, you would soon witness the Temple’s true wealth. You would begin to understand how its members can live in poverty and shun earthly rewards.

And a great part of this secret resides in Norea herself. For half a century she has been the hub of the Temple, its resident genius, greatest laborer, and lodestar in its invisible steeple. The hardwon devotion of the congregants to her, and their wholehearted faith in her preaching, can be observed in their transported faces as they stand swaying throughout the candlelit Sunday mass, listening elatedly while Norea, withered but fit and fiery with passionate love, strides between their seaweedlike forms and jubilates with her brittle hands outstretched. Her diaphanous voice floats through the heady altitudes of beatitude, trembling like a frail rocket launched through vacuum at transcendental plenum; it shreds like stained-glass music, and more than one worshipper has flickered and gone transparent at the high point of a harangue-paean to heaven, as Norea’s crystal cheeks glimmer with tears, as the whites of 100 eyes flicker with the dancing candleflames of estatic gnosis.

But in other moods, Norea serves as a Virgilian guide through outer darkness. During the more exclusive sermons, performing in the lower levels’ echoing geometries, she swoops from rhetorical heaven to the heights of despair, fulminating against our world’s filth, its insupportable injustices, its winnowing of the weak. At such times she crackles with inner electricity, hunch-backed, hands claws, white curls uncurling while she evokes Yaldabaoth, whom she calls ĊħĭļđőЬσțђ, challenging him and his yapping, teeming offspring with such temerity that the circumambient darkness slithers with hissing odors of iron-copper-blood-asphalt. Then the congregants suffer mightily, and some have shrieked or even swooned in those difficult moments before Norea completes her dive into the abyss, pops back up to the surface, and sails to the rescue on white-sailed triremes of uplifting language, her cutlass voice reviving the hot bright hope of battle—as long as they help her, she says. As long as they all work together. Finally she ends these advanced sermons by arming the congregants with explosive quotes, scriptural bullets of supreme wisdom which, as she constantly reiterates, do not contain the poison propaganda of conventionalizing hierarchy-enforcers inculcating the herd, but instead transmit the liberating gnosis of individuals writing to other awakened individuals, who form a suprahistorical ensemble of cooperating spirits in which every believer has her own unique role in saving the universe from itself. Every sister is equally significant, she concludes.

Somehow, though, all the Temple’s corridors seem to lead back to Norea herself, who has a vigor downright uncanny in a nonagenarian. Every day she pores over crumbling parchments and extracts fresh batches of revelations; every night she leads seminars and ceremonies and debates. Omnipresent, omnipotent, and omniscient, she organizes all efforts and orders all echelons. The adepts and congregants often have little to do with one another, but they all have close relationships with Norea, intense psychospiritual communions reinforced by monthly or even weekly meetings during which she dispenses sage advice on the most minute details of their personal lives. Frequently she has changed her parishioners’ minds and ways multiple times over, has shown them a new and broader perspective on existence, while they wring their hands and nod along feverishly. Some women she’s cracked open like oysters…

Perhaps one couldn’t be blamed for surmising that the Temple would not exist without Norea, that the Temple emanated from her and is just a local and pretentious neo-Gnostic cult led by a charismatic charlatan or madwoman—but in fact, Norea is so very enchantingly magnetic, so ensorcelling and so elephantinely memorious, precisely because her body and brain, as she imparts to the initiates, are the refined products of two millennia of eugenic mate-selection and matriarchal education by an unbroken bloodline of self-perfecting priestesses all called Norea. No wonder she appears almost supernatural, like a shameless, unstained angel and ultimate maternality come to protect, to educate, to liberate, to reveal the truth and the way out, to guide us on cosmic journeys! No wonder she, bred to evangelize, can never stop prodding, poking, palpating, prying into the essence of everything, with her restless, morally dissatisfied intellect, by turns challenging and praising, which drives away so many but mesmerizes the few! Which so obsesses and consumes those few!

And truly, a certain type does find Norea captivating: say, someone young and over-open, childlike, sensitive, and hopeful but also self-doubting, fearful, and confused, maybe with some artistic talent or a sideline in rescuing shelter animals; someone moved by love, worry, sunsets, God; someone who warmheartedly believes in good magic—a hothouse orchid of a person, with a vibrant, quivering blossom that withers away if even one condition for its growth is not met. A person, for example, like my mother in her youth.

Sad to say, such people suffer greatly in the Temple, for we must never forget that Norea, hymenopterously busy in her black jumpsuit, runs an apocalypse cell which posits that the End Times are just under the next calendar page. It’s entirely natural that more sensitive members might hyperfixate, scan the news for signs, pray weeping, quake in bed at night, or explode screaming out of nightmares. A few unlucky ducks might even become unable to live their lives, paralyzed with fears of cosmic Armageddon and of onerous eschatological responsibilities. Such a sufferer might even infect her own son with lifelong anxieties and an itching sense of doom—but can we really afford to fret over people who crack? Who said the End Times would be a picnic? Look around, as Norea suggests: forests of rockets bristle, financiers trade stacks of futures, deflated walruses wash up in the thousands while the ocean breathes a permachemical gurgle. Zombie hordes of insane entrepreneurs rove the streets and rave at what they sense is coming; some have met Satan in cocaine, some have become him, some have even eaten or surpassed him. Just who can stay cool?

Well, Norea can, and she can help you stay cool too, through the panacea of gnosis. In this case, the gnosis that every catastrophe has been foretold down to the most minute detail in the Temple’s scriptures, which are a veritable map of life and guidebook to redemption. These astounding documents—seven secret treatises handed down from mother to daughter, from Norea to Norea to Norea for thousands of years—accurately name and explicitly shame in advance all major horrors from the Church’s rise to the “Enlightenment” to industrialization and mechanized genocide, to the malignant insta-growth of the atomic bomb, whose cloud is not a mushroom but a tree of death, an offer of intimate knowledge of evil, and a signature, proof and promise from our ecocidal deity, who, eroded by waves of self-purifying Gnostics, is lashing out as he merges with eternal obliteration. So be brave! The scriptures say only one major cataclysm remains, and then we’ll all be blobbing in transcendental paradise.

Of course, a kvetching and dyspeptic doubter might try to claim that Norea’s scriptures were written more recently, after the events described, and most likely by Norea herself. Hah! Surely such a Sherlockian cynic would undergo a terrifying epistemological supercrisis were he blindfolded, made to drink the Water of Life, and ushered down to the Temple’s bunker’s final level, across the Hall of Winds and through seven locked doors to an oblong room with one wall made of bulletproof glass, where the former scoffer would drop to his fucking knees at the awesome sight of a dais holding two codices bound in soft leather, two holy relics the color of earth and craquelured like elderly faces, the right codex propped open on serried tiers of ancient Greek, the left on a scarlet and sepia illustration of Noah’s ark on fire. The sacred tomes would scintillate and throb, the pages would ruffle, and the ex-skeptic’s eyes would widen further than ever before, wide enough for the universe to climb right into his head, and suddenly he would briefly understand the ancient Greek, just before he passed out from the massed rapture of a hundred thousand brain-orgasms.

And even though you can’t have a surreal brain-bursting theophany and inrush of impossible xenoglossia every day, on the other days Norea can read aloud her translations, which are masterpieces of serene classical prose, lucid like cosmic aquariums and rippling with ideological rainbows. As comforting as the softest pillow, as finely ornamented as Gothic gables, and as radiant as the righteousness of all nine heavens, her translations of non-fictional fantasy illustrate in the lushest possible way the truth, what we should do, and how to elude death, knitting existential inquiries into swashbuckling adventures rich with memorable entities, surprising twists and poignant inversions of mainstream stories, and moreover with stunning new developments in Gnostic thought, reversing what other Gnostics reversed from Christians. This startling and gorgeous new world is what makes the congregants sob, as Norea wraps them in sonic cocoons decked with homilectic lovelinesses, illuminating their minds with the light cast by many-faceted allegories, by chandeliers of ideas hung with crystal prism-symbols of redemption. Yea truly, her scriptures hold the keys to the kingdom of heaven and could unlock all our minds, for their clear, accessible beauty and searing light would melt away the unclean rags of our earthly travails and clothe us in the garments of life, lofting us into realms of light, so that we might better glorify the child of the crown of the silence and give praise to the great Yeseus Mazareus Yezedekeus, and so on, and whatever.

But Norea refuses to publish.

III ~ The Triple-Male Child

Why won’t the high priestess publish?

When will Norea emerge and enlighten everyone?

Who will save our sickly species from the idiot-savant supernaturo?

I, for one, am haunted by these ghoulish questions. They ring my bed, pointing at me and hissing hot takes, and in my guilt-gassed dreams I accost Norea, gouging the slack skin under my eyes and groaning, “Speak, Norea! Speak out now, before I do something desperate and reprehensible!”

But her eidolon always goes out like a candle, smoking itself into dust.

At other times I roam sleepless in a billowing bathrobe around my roof, gazing up at high-rise dioramas of human lives, and comfort myself by murmuring scraps of wisdom from her scriptures. Though she never gave out copies, I did attend many, many, many sermons with my mother, and Norea had plenty of time to brand her language into my brain, to write her lessons in flames across the mountainsides of my imagination, in letters of emotional pain that to this day still drip magma into the wellsprings of my inner light. In theory, nothing should be easier than for me to write down her words.

So, faithfully I set pen to paper and start to work. But I never get far. Before long I slump back in nauseated horror from my writing desk, for the scriptures unrolling from my gel nib seem crude, laughable, and transparently untrue. Somehow my memories must be off, I must be mutilating her message in a million small ways I can’t detect. Strain and shrill as I might, the lingering sour-sweet stink of my voice taints the text, giving the impression that I’ve invented my own revelations. It’s a world-historical conundrum: in trying to speak directly, I end up blowing fog on the window of perception, till the reader sees no holiness, no angels or heavenly cities, only a semi-opaque reflection of my bedraggled and hag-ridden dude-face, stubbly with midnight shadow.

Troubled, I’ve given up many times. Permitting my weakness to steer, I decide to trust Norea, to resume my lowkey life and try to enjoy the scarce time left. And sometimes I feel all right. I stroll ferny roads, pet the occasional cat, make funny faces for my girlfriend. I wrap myself in delicate melodies, stroking my bristly cheeks, and forget everything but the present of the present… but then I lean out the windy window to sip some air, or I forget my own best advice and log into social media—and I hear the strident cries of billions of ungnowing spirits sinking into the gunk of oblivion, just salt in the soup of time; and my fists tighten; and I re-recognize that despite my natural cowardice and self-facing introversion it has fallen to me to bring gnosis to the masses. The salvation of everybody and everything depends on me figuring out how to exfoliate the Truth to the world at large, before we all get divided by the Zero.

A few days ago I grew restless again, drifting like a ghost ship around the uneasy ocean of my bed. Deep in the morning I groped after my phone and blearily booked a plane ticket. Earlier today the plane touched down in Toronto, where I rode trains and buses to the Temple in the Wasteland. Marching inside I confronted Norea and politely (I thought) asked her what was keeping her from sharing her spirit-saving scriptures. I may also have fired off a volley of questions, which she characterized as leading and insolent and not nearly as penetrating as I believed. As always this female Methusaleh, who looked made out of triangles, shrink wrap, and marbles, called me Boy and spoke with a scorn that I must have earned sometime I don’t remember. While her diamond-tipped stare drilled into me, she informed me that I had demonstrated an utter lack of understanding of her teachings and texts. I disagreed amiably enough, but her fragile form expanded glowing with the lush heat of her conflagrant wrath, into a sublime vision of terror and beauty, and she exiled me with the flaming sword of her voice from the august Eden of her presence.

Abruptly I was lying facedown in oily mud, with construction workers tugging at my shoulders. But even while stuck in that possibly toxic sludge, I already started chiding myself. I should have known: Norea can’t stand being glossed or misrepresented. She has always meticulously metered and meted out the flow of information. Never have I met anyone else who needs so much control.

And that’s when I had my biggest idea yet—my Copernican cataclysm.

By the time I was sitting up, with a hardhatted worker berating me in blocky English while his friend tried to calm him down, I knew for sure that my trip had not been in vain. My face was frescoed with iridescent mud, but my eyes must have been luminous twin beacons as I floated like a man in a dream back to my hotel room, at whose window seat I’ve written all these words, and from where I’m about to launch a fresh, unfair and sort of nefarious plan of attack.

Here's what I realized in the mud: I can lure Norea out. I can get her to erupt dramatically into the public eye. The trick is only to make her feel misunderstood by the masses. To get her laughed at and travestied by millions.

See, I’ve been going about this all wrong. I was afraid to distort her scriptures, but instead I must distort them on purpose.

May the Great Invisible Spirit have mercy on my soul, but—running athwart my highest inclinations, and offending against my most expensive principles—I do feel myself forced to debase her unparalleled storytelling and the elevated art of her majestical astral prose. Acting antichristly, I must twist her taste, debrief her brevity, and hurl horripilating hues; I must light the fuses of her gunpowder phrases till they explode into spiral cascades of self-caricatures, each larger than the last, waxing so absurdly, over-the-toply, stupidly ridiculous, so smirking and so irking that even if she reads this very sentence she’ll nevertheless feel compelled to forsake her hideyhole and strike my version down with saintly righteousness.

I’ll ruin Progenesis, story of the eternal realm. I’ll ruin ĊħĭļđőЬσțђ Alone, story of paradise and its populace. And as a fireworky finale I’ll ruin The Secret Gospel of Eve, story of Eve and her slap-happy, head-shredding apple trip.

Then, having fluffed up Norea’s stories, having beautified and entertainized them, I’ll collect ‘em in a book and sell its rights to the most predatorial bidder.

Maybe it can even reach the silver-blue screen? Hmm…

Yet, please remember that I don’t really want to be so cunning or infamous, much less to enrage Norea still more. Obviously I love and esteem her and would never have asked for a better shepherdess to herd my mother through many dreadful years of Armageddon obsession. I will never forget how wherever Norea pointed, the clouds blurred into laughing skulls, and how without her there to identify the darkness, we might have been dazzled by the stars.

If I could be granted one wish, I’d wish for Norea to submit her scriptures for ink-testing, so that through their astonishing verification she could acquire the necessary fame for her all-important mission. At last she could take the captain’s wheel of our society and, bellowing at us to row harder, harder, could pilot us between the Scylla of Abrahamism and the Charybdis of Atheism, toward the boundless fullness which pulsates beyond our crummy sky—our bargain-basement sky, with its ersatz sun radiating a janky imitation of true light.

The Secret Gospel of Eve will appear in two more parts, two citrous slices of rainbow ice-cream cake garnished with metal nuts and infused with exotic cathinones. Next week's part will cover the first two of Norea's treatises: Progenesis, following the disastrous creation of the universe, and ĊħĭļđőЬσțђ Alone, a ride on the slime god's shoulders as he morally descends toward the ultimate crime. The week afterward, we'll all congregate in Paradise and tail Eve through a fairytale catastrophe to the permanent blowing of her mind. The story gets about a thousand times wilder, so hang in there for the astounding denouement!

N.B.: Information on early Gnostic sects is generally lacking or biased; some groups may have been named, caricatured or even invented by their proto-orthodox enemies. Never doubt that this story is fiction in every single way. Any resemblance to contemporary Gnostic priestesses operating guerilla salvation units on the outskirts of Toronto is purely coincidental and nonactionable in any court of law whether earthly or celestial.

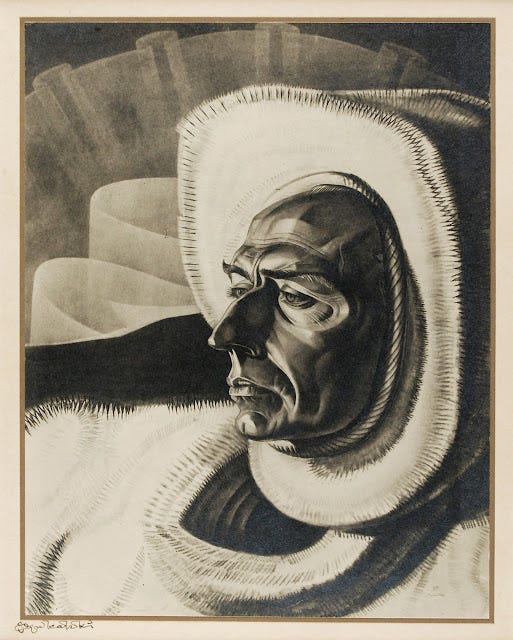

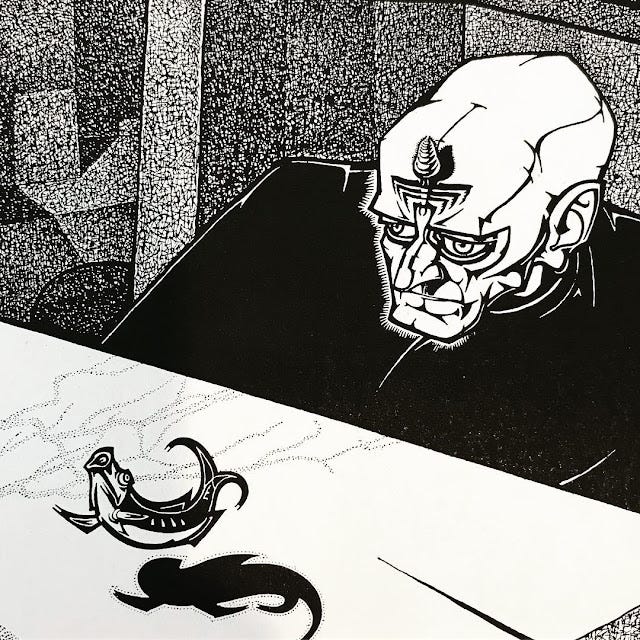

The images are taken from Stanisław Szukalski. They are not integral to the text.

All quotes, whole or defaced, are from Marvin W. Meyer's The Nag Hammadi Scriptures—read it for a good time.