The Spiraling Peril of Symbols

Metaphors We Live By | Carlyle's Sartor Resartus | Apuleius' The Golden Ass | the Greek Magical Papyri

Last week, I suggested that the pattern recognitions that fuel esoteric thinking—what some call the Barnum effect—seem to derive from a limited initial set of concepts, a sort of alphabet of fundamental ideas. A few days later, I remembered I’d read a relevant book, Lakoff and Johson’s Metaphors We Live By, which proposes that our more complex ideas are often organized through simpler conceptual metaphors derived from basic elements of physical or cultural experience.

Take Up vs Down, one of the most basic pairings. To a wild animal tramping around looking for food, Up means awake, standing, healthy and head; Down means asleep, lying, disabled and feet. To a tame animal manipulating language to pay her taxes, Up vs Down has lost some of its physical immediacy but swelled into an all-encompassing metaphorical pattern: she’s feeling up; she’s feeling down. Stocks are up. Onward and upward. Something’s going down. Gain, victory, and accession correspond to Up; loss, defeat, and resignation are Down. The celebrity rises and falls. Etc. Our embodied cognition has lent us the spatial composition of thoughts.

Look for these structuring metaphors in religion and mysticism and you’ll find them immediately. Take the idea of Up as Ascent: climbing the Sephiroth or the Neoplatonic chains of worlds, going up and down in the cycle of reincarnation. Heaven is up; Hell is down. Of course, there’s more going on in, say, Astrology, than just metaphors on bodily experience, but if you look past the symbols, at what the horoscopists say to do—keep your chin up, take the straight path, fight for someone’s love—you’ll see the ancient metaphors lurking. And although there is a great gap between paradigms like Up vs Down and the Zodiac, on the other hand it’s not hard to imagine those twelve mostly animal signs as hailing from a more complex stage of pattern identification. At some point in deep history, the first simple symbols, derived from our bodies, must have set off a cascade of ever more involved symbols, tiers of concepts layering on one another, each level more complicated than the last, building language, science, esotericism, ranging from accurate maps of meaning to the wildest dreamiest speculation built on the freest of associations.

Maybe we can say that epistemology recapitulates ontology. In my own case and mind, I sense this cumulative pattern recognition whenever something I’m learning interlocks with my older notions and a higher pattern emerges. Knowledge modifies knowledge, and the fractal of my comprehension makes another lap up its spiral. This feeling is unfortunately independent of the truth of what I’m realizing—some of my most memorable epiphanies, eurekas I couldn’t get over for years, turned out to be mistaken. I might chase the exaltation of piling patterns atop patterns, but my stilt-house of knowledge will always be spindle-legged, cantilevered, wonky and ridiculous, built on the underlying island of my childhood, and permanently on the verge of sinking into stagnance. Metaphors and other symbols can be dangerous, see. They can be cages. And they can obliterate their origins, coming to seem like truths that inform all things. When a new symbol is born, it is dazzling. We are ensorcelled by our images, which we perceive only through other images.

Or so I picture. I do believe in useful degrees of truth, it’s just that every individual mind is a shambling blind horse-cart with wheels falling off underneath while wild fires burn above. I’m being sincere when I say that the rainbow flames of our brains are magical, hypnotizing, beautiful and profound, but atop the dodgy contraption of our bodies rolling down the streets of our days, we can’t make it all the way down a long idea without crashing at least once, burning down other ideas and scorching the conceptual bricks. As the mind moves through its own mental space, it creates and destroys what it moves through, paving and decorating its eccentric orbits, caught in a heavy feedback loop with reality, always moving away from and drawn back to matter, without ever managing to look it directly in its being. The isolated mind is an eye and not a mirror. Even a genius is often wrong. The wisdom of the species is aggregate. We are more antlike than we realize.

I’ve been having these feeble, crooked, limping half-thoughts all week, since I’ve been reading and wrestling with Thomas Carlyle, who addressed these ideas and more in his 1834 philosophical meta-novel Sartor Resartus. He came down on rather a different side of the debate, proposing (perhaps part satirically?) that symbols, or ‘clothes,’ are the human window onto infinity. Though I can’t say I loved his book or even agreed with him, Carlyle is always a challenging, heavyweight stylist capable of giving skeptical readers black eyes. Impressively, he anticipated the embodied-cognition argument put forward by Lakoff and Johnson:

‘Language is called the Garment of Thought: however, it should rather be, Language is the Flesh-Garment, the Body, of Thought. I said that Imagination wove this Flesh-Garment; and does she not? Metaphors are her stuff: examine Language; what, if you except some few primitive elements (of natural sound), what is it all but Metaphors, recognised as such, or no longer recognised; still fluid and florid, or now solid-grown and colourless? If those same primitive elements are the osseous fixtures in the Flesh-Garment, Language, – then are Metaphors its muscles and tissues and living integuments. An unmetaphorical style you shall in vain seek for: is not your very Attention a Stretching-to?

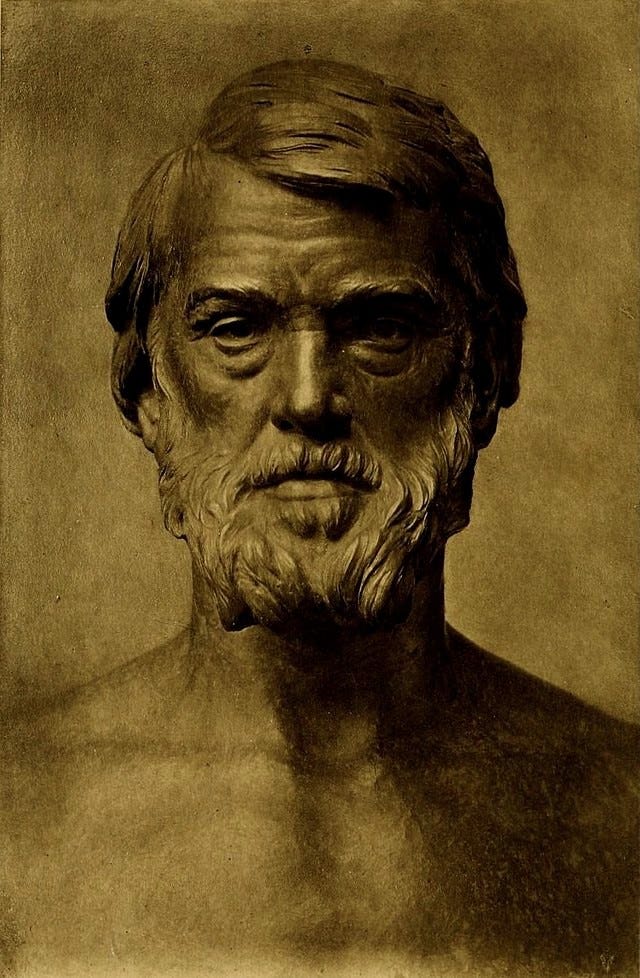

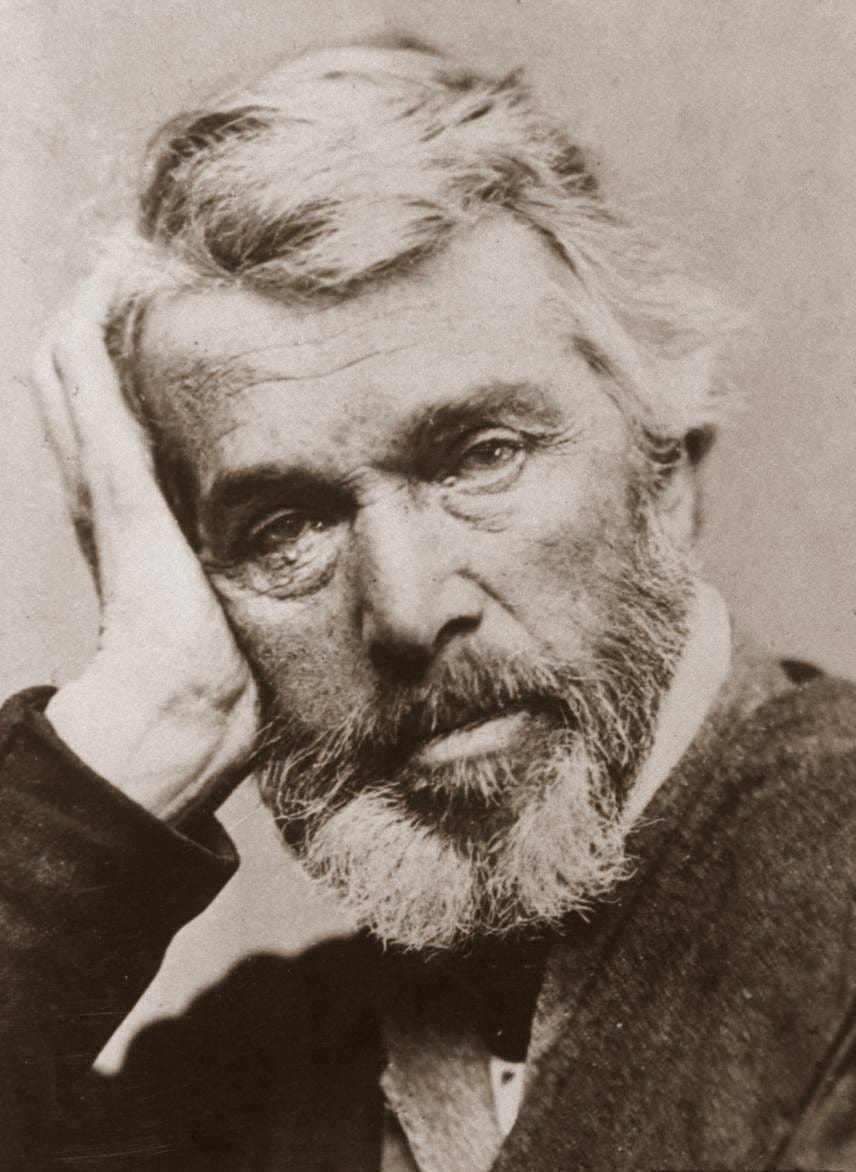

Jagged, waggish, and cartoonishly erudite, Carlyle packed a basketful of punches whenever he invited the reader to his fistic picnics (and would not hesitate to write sentences just as ridiculous). In the 19th-century he was one of the most famous living writers; now his work has fallen from favor, and most of what remains is the monument of his idiosyncratic character and the works of the many intellectuals he influenced. And rightfully so. Carlyle, a coruscating craftsman and heavyweight tastemaker of the Victorian age, with something original to say about almost any subject, ultimately fell victim to his symbols. Structural metaphors, deeper than he himself was able to perceive, allowed him to annihilate his actual connection to the reality in front of him. His pattern recognition, caught in a lockstep of imagery, prevented him from ever recognizing himself. His philosophy was an angry lullaby, and he sang himself to sleep, to a restless, tormented sleep.

Beginning as a writer on German romantic literature and philosophy, Carlyle grew into a lodestar for the Victorians, the “undoubted head of English letters” and a “secular prophet.” His Wikipedia article records an operatic fusillade of fullthroated praise, the heads in the canon lining up to belt their tributes. Thoreau called him a master unrivalled of the English language. Trollope called him Homer in prose. Norton said he was nearer Dante than any other man. Ruskin meant to throw himself into “mere fulfilment of Carlyle’s work.” Emerson once described himself as Lieutenant to Carlyle’s General in Chief. Borges, as a teenager, memorized entire pages of Sartor Resartus. Darwin considered him "the most worth listening to, of any man I know." George Eliot wrote: “It is an idle question to ask whether his books will be read a century hence: if they were all burnt as the grandest of Suttees on his funeral pile, it would be only like cutting down an oak after its acorns have sown a forest. For there is hardly a superior or active mind of this generation that has not been modified by Carlyle's writings; there has hardly been an English book written for the last ten or twelve years that would not have been different if Carlyle had not lived.”

His writing helped create the English bildungsroman. His discussion of symbols influenced French symbolism. His medievalism influenced the spirit of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts Movement. He’s in Young English conservatism, Christian socialism, Marx and Engels, Gandhi. Martin Luther King quoted from Sartor Resartus. Gauguin painted Sartor in a portrait. Debussy imagined a missing chapter, “The Relationship of the Hat to Music.” Lady Eastlake said he had the best laugh she’d ever heard. People said things like, “His eyes, which grew lighter with age, were then of a deep violet, with fire burning at the bottom of them, which flashed out at the least excitement. The face was altogether most striking, most impressive in every way.”

So what happened? Well, A Book is a Deck of Windows is my eccentricities blog and not a deep dive into research and philosophy, and I’m really only interested in Carlyle’s writing (do not treat this post as a fair introduction to him or his ideas). But in this limited space I’ll mention that Carlyle’s star fell for two reasons. One is that some of his signature ideas—the Great Man theory of history, which states that great men are the shapers of history, and the Heroarchy, the theory of government by heroes—fed into fascism. Among his admirers was Goebbels, who read Carlyle out loud to Hitler in the Führerbunker as they awaited the end. Also, Carlyle wrote a pamphlet called “Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question,” later revising “Negro” to “Nigger,” and tried to explain how to reform slavery’s abuses and “save what is precious in it.” And he hated Jews so much that he could be seen as a retroactive Zionist—he suggested a return to Palestine in order to get them out of his country.

You can probably guess the other, less ideological reason he fell from the limelight: his personality. Carlyle, such an impressive and charming man, expert at producing an effect on other people, was outed by his first biographer and his wife’s letters as a unrepentant bitter whinger, a lifelong sufferer from dyspepsia who tormented his talented and intelligent spouse and couldn’t even perform his husbandly duties: this raging, majestic worshipper of heroes seems to have been impotent. Rarely has someone’s personality been such an inverted image of their insufficiencies. It might help to know that as a child he was savagely bullied till he learned to fight.

But don’t forget the paeans from the modern pantheon of intellectuals. Carlyle is a worthwhile, even a heroic read. His writing, at least, embodied his philosophy. He remains a knotty, polyform thinker who forces his readers to become smarter if only to contradict him. And his style, known as Carlylese, is and will always be astonishing. Carlylese is all vim and visuals all the time, feverish and pugilistic, rhapsodic, speculative and exhortatory and nonstop inventive, with “apostrophe, apposition, archaism, exclamation, imperative mood, inversion, parallelism, portmanteau, present tense, neologisms, metaphor, personification, and repetition.” He’s the 26th most-cited author in the O.E.D., with 16% of his coinages still being in use today. And it’s his style, which I’d encountered in his famous prose epic The French Revolution, that convinced me to read Sartor Resartus.

Sartor Resartus, which means “The Tailor Retailored,” is a striped hybrid beast of autobiography, satirical novel, pseudo-criticism, and actual philosophy, but it pretends to be a monograph on the life and thought of a German philosopher and professor called Diogenes Teufelsdröckh (“Zeus-born Devil’s-dung”), who has written a treatise on clothes. Much of Sartor Resartus consists of the fictional editor pondering, debating, contextualizing, summarizing or quoting the philosopher’s work on clothing, which turns out to be an all-encompassing metaphor for life, knowledge, humanity.

‘Men are properly said to be clothed with Authority, clothed with Beauty, with Curses, and the like. Nay, if you consider it, what is Man himself, and his whole terrestrial Life, but an Emblem; a Clothing or visible Garment for that divine Me of his, cast hither, like a light-particle, down from Heaven? Thus is he said also to be clothed with a Body.

The metaphor of clothing must have been inspired by Jonathan Swift, whom Carlyle loved so much as a student that he had his friends call him “Old Jonny.” Swift’s Tale of a Tub, which I read a few months back, contains an allegory of The Reformation in which the three main branches of Western Christianity (Catholic, Protestant, and Anglican) are represented by three sons who have inherited sensible clothes which will serve them all their lives, provided that they never, ever alter the cut. Naturally as soon as the old man croaks the three sons promptly set about altering their outfits—that is, their Christian doctrine—according to whatever latest fashion strikes their weak-willed fancies. But look closely: it’s not that clothes stand in for artificiality or lack of substance; it’s that one must wear the right clothes. All existence is clothing. From this seed idea, Carlyle fans up an entire book, using the philosophy of clothes to discuss the relation of reality to the divine, illusion to truth, finite to infinite.

Clothing, for Carlyle, is a high-level conceptual metaphor, derived from advanced embodied experience. But it’s not the symbol that defeated him.

The first third of Sartor Resartus, after opening with fake reviews and many Shandean gags and pokings, follows the supposed editor summarizing the philosophy of clothes. The second third, supposedly based on bags of paper scraps that the editor has assembled into a vague and partial biography, is full of fanciful and questionable events that recast Carlyle’s own life with a coy, eyelash-batting mixture of self-satire and grandiosity. A mysterious man drops Teufelsdröckh off as a baby, then despite the best efforts of his teachers the future philosopher grows up to be a genius, falls precipitately in love with a “goddess of flowers” and of course is monstrously disappointed—though honestly, the specific events are almost never as interesting as the writing itself, fittingly enough for a book that praises clothes as manifestations of truth. Carlyle’s style can be downright angelic, aureate, afloat in white robes. Here is the young German philosopher reading the alphabet as if he’s going to church:

‘Thus encircled by the mystery of Existence; under the deep heavenly Firmament; waited on by the four golden Seasons, with their vicissitudes of contribution, for even grim Winter brought its skating-matches and shooting-matches, its snow-storms and Christmas carols, – did the Child sit and learn. These things were the Alphabet, whereby in after-time he was to syllable and partly read the grand Volume of the World: what matters it whether such Alphabet be in large gilt letters or in small ungilt ones, so you have an eye to read it? For Gneschen, eager to learn, the very act of looking thereon was a blessedness that gilded all: his existence was a bright, soft element of Joy; out of which, as in Prospero’s Island, wonder after wonder bodied itself forth, to teach by charming.

In Swift’s case, the parody tests readers, forcing them to make sharper analyses. But where Swift doesn’t offer any affirmation, Carlyle has a much bigger project in mind, and in the final third of the book he turns to the heart of the philosophy of clothes and makes his grand statement on the world, politics, God. At this point his most serious influences move to the fore: Shakespeare, Goethe, and the Bible; and parody inflates into praise. In the biographical section, Teufelsdröckh’s heartbreak had culminated in a scornful scoffing rejection of everything, a state of hopelessness and despair that he calls the Everlasting No, which is, at its heart, a denial of the divine:

To me the Universe was all void of Life, of Purpose, of Volition, even of Hostility: it was one huge, dead, immeasurable Steam-engine, rolling on, in its dead indifference, to grind me limb from limb. O the vast, gloomy, solitary Golgotha, and Mill of Death!

But this despair, incurred from a heart-wound, soon heals over and passes into indifference, and the good professor reaches what he thinks of as the Everlasting Yea:

‘there is in man a HIGHER than Love of Happiness: he can do without Happiness, and instead thereof find Blessedness! Was it not to preach forth this same HIGHER that sages and martyrs, the Poet and the Priest, in all times, have spoken and suffered; bearing testimony, through life and through death, of the Godlike that is in Man, and how in the Godlike only has he Strength and Freedom? … By benignant fever-paroxysms is Life rooting out the deep-seated chronic Disease, and triumphs over Death. On the roaring billows of Time, thou art not engulphed, but borne aloft into the azure of Eternity. Love not Pleasure; love God. This is the EVERLASTING YEA, wherein all contradiction is solved; wherein whoso walks and works, it is well with him.’

The Everlasting Yea, huh? Well, what’s he saying Yea to? All life? All that is human? Nah. “Love not pleasure: love God.” The Yea is his name for the spirit of faith in God, the joyful Yay of belief. Carlyle had said he was no longer Christian, that no doctrine could know the true nature of God and that to possess such knowledge is impossible, yet he still took for granted an all-powerful creative force behind everything, an obviously post-Christian lord rolled back to the Platonic roots:

Striking it was, amid all his perverse cloudiness, with what force of vision and of heart he pierced into the mystery of the World; recognising in the highest sensible phenomena, so far as Sense went, only fresh or faded Raiment; yet ever, under this, a celestial Essence thereby rendered visible: and while, on the one hand, he trod the old rags of Matter, with their tinsels, into the mire, he on the other every where exalted Spirit above all earthly principalities and powers, and worshipped it, though under the meanest shapes, with a true Platonic Mysticism.

The quote says it all. While announcing his Yea to the exalted spirit, the professor treads “the old rags of Matter.” The last volume of Resartus is still to come, and as a point of fact Carlyle will devote most of it to saying No, No, No, to pretty much everything that actually exists. Fashion, society, science, space and time, dandies and peasants, everybody who isn’t a king? Diss and dismiss ‘em—Carlyle did. This extraordinarily talented and physically striking man, this brilliant and belligerent puritan whose willy did not work, unable to enjoy life or treat his spouse decently, preferred to fantasize about perfect heroic men under a perfect heroic God. To say Yea to a flimsy, pathetic fantasy of final power, a hypermasculine intellectualization of the ultimate hero, greatest and strongest of all, phallus who inseminated the cosmos. Carlyle, hypnotized by cultural clusters of symbols—Man, the Great Man, Man as God, Maker as Creator—projected onto the universe patterns abstracted from his animal experience, and his refined image of paternal, perfected glory was so powerful that he went blind to life. The idea of perfection destroyed the human. A bullied child had made an icon of the biggest man ever, and briefly he managed to convince others to drop their knees and worship by his side. It takes a weak, sick, dyspeptic and impotent person to make such an idol out of strength. Just ask Nietzsche.

But Nietzsche managed to affirm existence. Carlyle didn’t. Can a man do without happiness, as he proudly pronounced? Well… would anyone here like to be him?

As for me, I don’t think in terms of heroes, and I certainly wouldn’t call ermine dominators heroic. I don’t abase myself before daddies. I like our world's buzzing, booming profusion of tastes and types, and I can empathize with Queen Victoria when she wrote in her journal of "Mr. Carlyle, the historian, a strange-looking eccentric old Scotchman, who holds forth, in a drawling melancholy voice, with a broad Scotch accent, upon Scotland and upon the utter degeneration of everything."

In my last post I discussed Nijinsky, another man who had powerful emotions and confused himself with God. He had more of a sense for others; his favorite verb, if frequency of use is any indication, was “feel.” I wonder what he would have said to Carlyle? Maybe:

You are a spiteful man. You are not king. But I am. You are not my king, but I am your king. You wish me harm, I do not wish harm. You are a spiteful man, but I am a lullabyer. Rockabye, bye, bye, bye. Sleep in peace, rockabye, bye. Bye. Bye. Bye.

—Man to man, Vaslav Nijinsky.

Too far? I’ll pass the mike to the philosopher Alphonse Lingis, writing in Dangerous Emotions, and let him imply a richer, realer, more sunlit philosophy of clothes:

The ceremonies and etiquette with which courtship was elaborated in the palaces of the Sun King were not more ritualized than the courtship of Emperor penguins in Antarctica, the codes of chivalry in medieval Provence not more idealized than the spring rituals of impalas in the East African savannah, the rites of seduction of geishas in old Kyoto not more refined than those of black-neck cranes in moonlit marshes. Humans have from earliest times made themselves erotically alluring by grafting upon themselves the splendors of the other animals, the filmy plumes of ostriches, the secret luster of mother-of-pearl oysters, the springtime gleam of fox fur. Until the gardens of Versailles, perfumes were made not with the nectar of flowers but with the musks of rodents. The days-long songs of whales and the dance floors cleared of vegetation and decorated with shells and flowers that birds of paradise make for their intoxicated dances exhibit the extravagant erotic elaborations far beyond reproductive copulation in which humans have joined with the other animals.

After Sartor Resartus, I checked in with the antique pagans for some relief and relaxation. I much prefer their lusher, funner and sunnier company, with their love of sensation, earthliness, feast. My next read was the only surviving Roman novel in Latin, Apuleius’ The Golden Ass, which was written around 170 CE. It’s especially notable for the bizarre style, as Jack Lindsay writes in the introduction to his translation (via Wikipedia):

Take the description of the baker's wife: saeva scaeva virosa ebriosa pervicax pertinax... The nagging clashing effect of the rhymes gives us half the meaning. I quote two well-known versions: "She was crabbed, cruel, cursed, drunken, obstinate, niggish, phantasmagoric." "She was mischievous, malignant, addicted to men and wine, forward and stubborn." And here is the most recent one (by R. Graves): "She was malicious, cruel, spiteful, lecherous, drunken, selfish, obstinate." Read again the merry and expressive doggerel of Apuleius and it will be seen how little of his vision of life has been transferred into English.

Sarah Ruden's recent translation is: "A fiend in a fight but not very bright, hot for a crotch, wine-botched, rather die than let a whim pass by—that was her.

Unfortunately I can’t read Latin, and I read the Robert Graves translation, so I’ll have to focus on the story. (I wish I’d had Ruden’s translation, that sample is fantastic!)

This proto-picaresque very-tall tale is nominally about a man so eager to try magic that he accidentally turns himself into a donkey, but Apuleius was a yarn-spinner, a chuckly raconteur who constantly bounced off into tangential tales and anecdotes, and the book’s most famous section doesn’t even concern the golden donkey, but Psyche, the world’s most beautiful woman. She marries Cupid, lives in his castle with invisible servants and makes love to him in the dark, but then inevitably loses him and must brave many obstacles to recover her divine lover:

‘Psyche started at once for the top of the mountain, which was called Aroanius, thinking that there at least she would find a means of ending her wretched life. As she came near she saw what a stupendously dangerous and difficult task had been set her. The dreadful waters of the Styx burst out from half-way up an enormously tall, steep, slippery precipice; cascaded down into a narrow conduit which they had hollowed for themselves in the course of centuries, and flowed unseen into the gorge below. On both sides of their outlet she saw fierce dragons crawling, never asleep, always on guard with unwinking eyes, and stretching their long necks over the sacred water. And the waters sang as they rolled along, varying the words every now and then: “Be off! Be off!” and “What do you wish, wish, wish? Look! Look!” and “What are you at, are you at? Care, take care!”. “Off with you, off with you, off with you! Death! Death!”

Referenced often in the post-Renaissance history of art, the tale of Cupid and Psyche is as beautiful as anything from Ovid, albeit weirder. But there is another, funnier reason that this one story is better known than the rest of the Golden Ass—which is that the rest of the book is incredibly and hilariously filthy. The only surviving Latin novel is a shameless, even joyful tour through a narrative Sodom and Gomorrah, all sex, murder, sex, witchcraft, and more sex, told with a straightforward mix of laughter and appetite, like a sloshed carouser’s tall tale over an amphora:

“'Dear Fotis,’ I said, ‘how daintily, how charmingly you stir that casserole: I love watching you wriggle your hips. And what a wonderful cook you are! The man whom you allow to poke his finger into your little casserole is the luckiest fellow alive.”

Can't you hear that antique grin? That scene is the least of it. Later those two happily copulate; first the standard way, then the backdoor. At a different point witches rip out a man's heart, replace it with a sponge, and piss on his friend. A corpse comes briefly back to life to confirm his wife poisoned him to hide her adultery. A randy stepmother—well, do I need to elaborate? A rich woman, bored of lesser perversions, has sex with the donkey. A cuckold comes home, finds his wife's lover still there, and reasons that he and his wife share everything and so it's only fair if he sodomizes the unlucky, trembling youth all night—this is a Roman joke! Laugh! The only Christian character gets drunk on the wine of the Eucharist… And there are even ecstatic charlatans who seem to have invented head-banging long before the first metalhead ever did the devil horns in his mother’s womb:

“After passing through several hamlets we reached a large country-house where, raising a yell at the gate, they rushed frantically in and danced again. They would throw their heads forward so that their long hair fell down over their faces, then rotate them so rapidly that it wheeled around in a circle. Every now and then they would bite themselves savagely and as a climax cut their arms with the sharp knives that they carried...

After all these racy misadventures, what happens? Dostoevsky would surely fume primly and send the ass to a labor camp to live through his sins, but instead Apuleius has the golden donkey meet the mother goddess Isis, who rises out of the night sea and instructs him to become her priest. She’s as lovingly depicted as a Madonna by Velazquez or a Salomé by Moreau; I miss all the paintings that were never made of her.

Her long thick hair fell in tapering ringlets on her lovely neck, and was crowned with an intricate chaplet in which was woven every kind of flower. Just above her brow shone a round disc, like a mirror, or like the bright face of the moon, which told me who she was. Vipers rising from the left-hand and right-hand partings of her hair supported this disc, with ears of corn bristling beside them. Her many-colored robe was of finest linen; part was glistening white, part crocus-yellow, part glowing red and along the entire hem a woven bordure of flowers and fruit clung swaying in the breeze…

The Golden Ass is not some lofty masterpiece, but it is entertaining and earthly, imaginative and perhaps even instructive for someone living in the long shadow of Christian morality. Contrast Apuleius, who really was a priest of Isis, with St. Augustine or Paul. Those two suffered from nagging guilt after they converted, wrestling their thorny consciences till they died. Particularly of note is Paul: as a Jew he had considered himself blameless before the law, having made the proper sacrifices to atone for his sins, but as a Christian he could never be sure he was sinless, saw himself as fundamentally small and powerless, and had no route to forgiveness except through Jesus. Apuleius, though—he converted, participated in magic rites, and continued to get laid, sleep well, bellylaugh and tell fun stories, never surrendering his zest for life and life’s pleasures. Carlyle could have learned something from him.

I also finished reading The Greek Magical Papyri including the Demotic Spells, edited by Hans Dieter Betz. Usually I read either obsolete scriptures or treatises, which are generally written either by serious people or serious pretenders, but the Greek magical papyri, dating from about 100 BC to 400 CE, are a corpus of randomly assembled documents containing spells, rites, liturgies and oracles, and I was surprised at first by the relatively high quotient of obvious bullshit. At least a few papyri were clearly commercial objects dashed off by charlatans or dilettantes in order to wrangle a quick buck from the gullible, their composers mangling the names and attributes of gods or including meaningless or fake quotations. Meanwhile, other scrolls are just badly written: the poetic meter is faulty, the sense is pocked with holes, and they’re generic, tedious, and pretentious. For example, they assign simple ingredients elevated names: “Tears of a Hamadryas baboon" for "blood of a spotted gecko," "lion semen" for human semen, “Blood of Ares" for purslane.

At other times, though, a few papyri show glints of literary talent and mythical splendor. Maybe those scribes were also cynically forging a magic document to make a few extra coins, but maybe they believed what they were writing—after all, crazy, freewheeling, speculative beliefs abounded in Greco-Roman Egypt, the source of Hermeticism and so the ancestral land of much modern esotericism. Magicians do convince themselves. Either way, I stumbled across a few beautiful imaginations, such as in this papyrus where the caster is to make an “inquiry of a lamp”:

Are you the unique, great wick of the linen of Thoth? Are you the byssus robe of Osiris, the divine Drowned, woven by the hand of Isis, spun by the hand of Nephthys? Are you the original bandage which was made for Osiris Khenty-amenti? Are you the great bandage with which Anubis lifted his hand to the body of Osiris the mighty god? It is in order … to look into you so that you may make reply concerning about which I am asking here today, that I am bringing today, O wick. (If not doing it is what you will do, O wick, it is in the hand of the black cow that I am burning you. Blood of the Drowned One is what I am giving to you for oil. The hand of Anubis is that which is laid against you. The spells of the great Sorcerer are those which I am reciting to you.) And so that you bring me the god in whose hand the command is today, so that he tell me an answer to everything about which I am inquiring here today, truly, without falsehood. O Nut, mother of water, O Opet, mother of fire, come to me, Nut, mother of water; come, Opet, mother of fire; come to me IAHO. You should say it whispering exceedingly. You should also say: “ESEKS POE EFG CHTN” (also called “CHT ON”), seven times.

This is timelessly cool. It has a consistent goth-Egyptian aesthetic. It plays fluidly with imagery, turning the wick into linen, then into silken byssus robe, then a bandage, while interweaving the names of gods. Black cow, Blood of the Drowned One, hand of Anubis. The blast of nonsense syllables, crushed language from no tongue, voces magicae. So aesthetic! And if results are not forthcoming, then the papyrus escalates the situation, instructing the aspiring magus how to impress, browbeat, and threaten the poor lamp:

I will not give you fat, O lamp. It is in the belly of the female cow that I shall put you, and I shall put blood of the male bull after you, and I shall put your hand to the testicles of the enemy of Horus.

It takes a certain ruthlessness to be a wizard—but I think it’s worth an experiment. Maybe I can bully a candle into spitting out the lottery numbers.

Religious texts are rarely fun to read all the way through. I sift and pan, sift and pan, till I have a small handful of weird metaphysical crystals. From the papyri I extracted about twenty samples for surreal fiction, for quotation, parody, pastiche, and other uses in my writing. Everything is material, if you give it a little twist. I know if I keep such images around they’ll almost certainly slip into my stories:

The sound-eye is what I ate.

After saying this, you will see the doors thrown open, and seven virgins coming from deep within, dressed in linen garments, and with the faces of asps. They are called the Fates of heaven, and wield golden wands.

Born of blood, shedding blood / putting out roots, androgynous, ANTHROROCH, born with blood saffron-dyed, with gold arrows, golden-haired, dog-faced baboon.

And check out this legend of creation—it’s so crude and strange that I feel it must be some secondhand story, something the scribe was told or read and which existed somewhere else in a more fleshed-out form. It reads like a crude drawing looks:

When the god laughed a seventh time Psyche [Soul] came into being, and he wept while laughing. On seeing Psyche, he hissed, and the earth heaved and gave birth to the Pythian serpent who foreknew all things, so that god called him ILILLOU ILILLOU ILILLOU ILILLOUI ITHŌR MARMARAUGĒ PHŌCHŌ PHŌBŌCH. Seeing the serpent, the god was frightened and said, "Pop, pop, pop." When the god said, "Pop, pop, pop," an armed man appeared who is called DANOUP CHRATOR BERBALI BARBITH. Seeing him the god was again terrified, as seeing someone stronger [than himself, fearing] lest the earth had thrown up a god. Looking down at the earth, he said “IAŌ.” From the echo a god was born who is lord of all. The preceding man contended with him, saying, “I am stronger than this fellow.” The first god said to the strong man, “You come from the popping noise, and this god comes from an echo. Both of you will have charge of every need.” The pair was then called DANOUP CHRATOR BERBALI BALBITH IAŌ.

Finally, the following discussion of necro-theology lit a vague but exciting fire far back in my imagination—I don’t have any clear idea of what yet, but I feel that niggling tingle that means one of my tiny, jabbery notions is about to ambush me…

[I]t is characteristic of the Hellenistic syncretism of the Greek magical papyri that the netherworld and its deities had become one of its most important concerns. The goddess Hekate, identical with Persephone, Selene, Artemis, and the old Babylonian goddess Ereschigal, is one of the deities most often invoked in the papyri. Through the Egyptianizing influence of Osiris, Isis, and their company, other gods like Hermes, Aphrodite, and even the Jewish god Iao have in many respects become underworld deities. In fact, human life seems to consist of nothing but negotiations in the antechamber of death and the world of the dead. The underworld deities, the demons and the spirits of the dead, are constantly and unscrupulously invoked and exploited as the most important means for achieving the goals of human life on earth: the acquisition of love, wealth, health, fame, knowledge of the future, control over other persons, and so forth. In other words, there is a consensus that the best way to success and worldly pleasures is by using the underworld, death, and the forces of death.