Two Visions of Cosmic Architecture

Swedenborg's Heaven and Hell | The raving goddess, Kircher's prismatic angel, and Lautréamont's cannibal god | Alan Moore and Promethea | A Goodnight Mosaic

Heaven and Hell by Emanuel Swedenborg

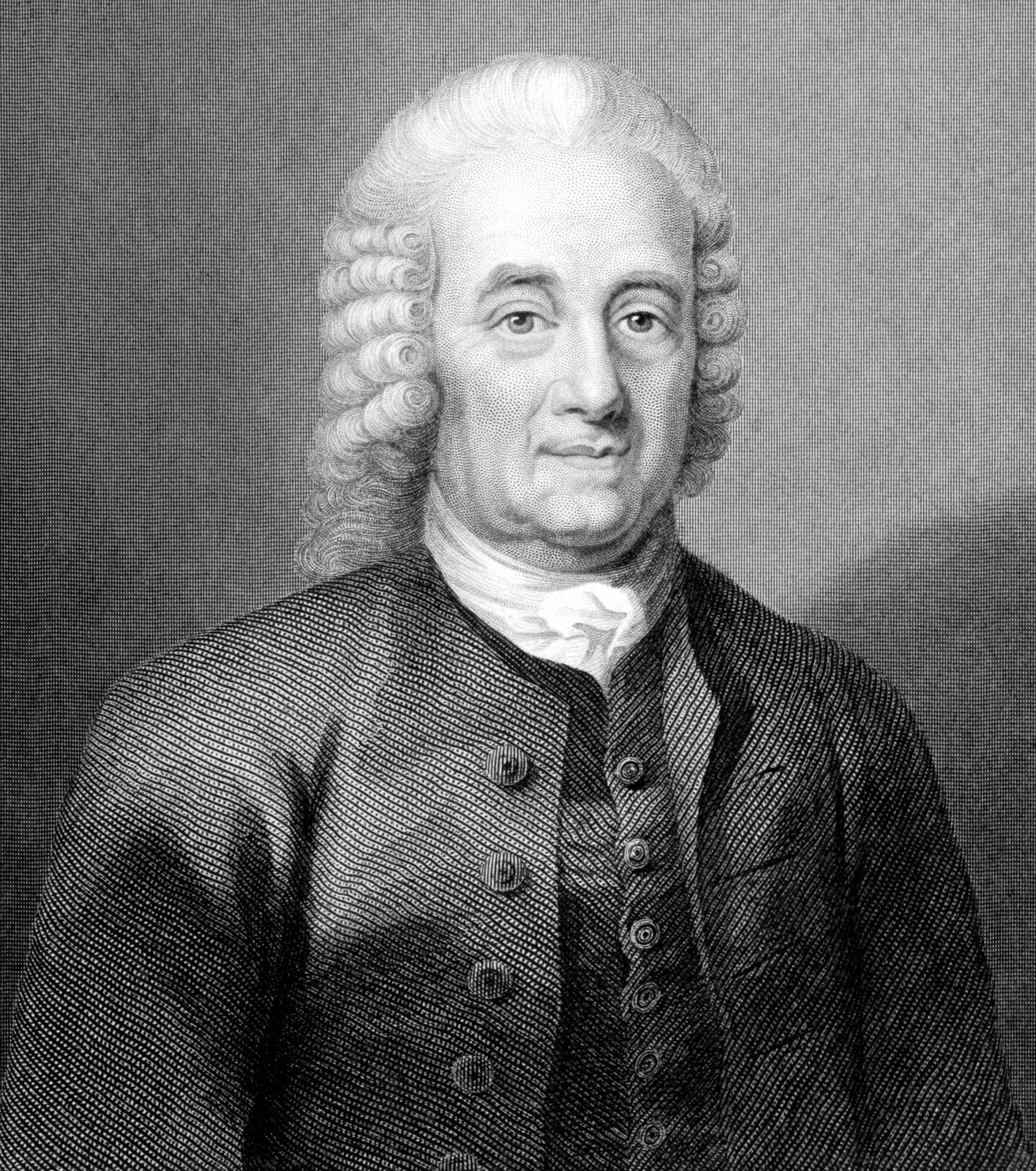

Emanuel Swedenborg was an 18th-century Swedish baron and prominent scientist who, at the age of 53, was ambushed by visions. He was thrown off his bed and onto Jesus’ chest; in a tavern’s backroom he glimpsed the tiers of hell. He even went through a pseudo-death where his heartbeat was connected to the heavenly kingdom, and angels drove spirits away from his pseudo-corpse. Soon he started writing at a terrific rate, producing thousands of pages which eventually formed the basis for his eccentric version of Christianity. At first he published his books anonymously, but his visions became famous in his lifetime, and there are notorious tales of his ESP, such as the occasion when he sensed a giant fire happening ten days’ ride away and announced the disaster to a bemused dinner party.

Kant was briefly a fan, so was Blake, and Swedenborg’s visionary, psychologized Christianity, which incorporates ideas from Neoplatonism, exerted a hallucinatory influence on Romanticism. Some churches based on his doctrine still survive, but his most lasting contribution was to Western occultism, where he helped inspire both Spiritualism and the scientistic pretensions common in New Age thought.

Personally, I find him funny. Dryly hilarious. Unlike the scruffy and impoverished St.-Anthonic visionaries one thinks of as communing with angels, Swedenborg was a dignified patrician and successful man of the world, and he had luxurious visions of unearthly palaces, courtyards, and parks where he chatted with cultured angels while they politely diagrammed the cosmos. This august aristocrat, both utterly dotty and utterly proper, never explained himself less than elegantly, calmly expounding and defending his insane yet coherent and well-ordered ideas. Heaven and Hell, which I read in a translation by George F. Dole, is accessible, lucid, and scholarly, with hundreds of carefully annotated references to Swedenborg’s other works and scripture; it’s only that all his sources are angels.

To some extent, we can determine what heaven’s form is like on the basis of what has been presented in the preceding chapters—that heaven has a basic similarity in its greatest and its smallest instances (§72); that therefore each community is a heaven in lesser form, and each angel in least form (§§51–58); that as heaven as a whole resembles a single person, so every community of heaven resembles a person in lesser form and every individual angel in least form (§§59–77); that the wisest people are at the center, with the less wise around them all the way to the borders, and that the same holds true for each community (§43); and that people who are engaged in the good of love live along the east-west axis and people who are engaged in truths that derive from the good along the south-north axis, which also holds true for each community (§§148–149).

Unfortunately for this well-dressed gladhander of seraphim, I am no wellwisher come to lay an amaranth at the foot of his tomb. I’m not interested in summing up his dogma or examining his place in the world of ideas. I am a concept burglar, and I pillage oddball scriptures to scavenge magic fuel for my imagination. What caught my attention in this Enlightenment boffin of the afterlife?

Well, I’ve always been partial to angelology…

According to the beatific baron, all angels and demons were once humans. There is no redemption from hell: after death you become either angel or demon and that’s it, no way out—though angels do progress through levels of purification, becoming ever closer to God. Heaven is ceaselessly active, everyone shares their bliss with one another, and angelic life is devoted to worthwhile actions. God doesn’t care about praise or glorification; angels are made happy through service and nothing but service… but also, angels have swanky pads, jeweled palaces in heaven, and wear rad outfits that reflect their intelligence. The most intelligent wear clothes like flame, the less intelligent pure white, and those still less intelligent colored clothes. Yet the inmost angels, closest to God—those holiest ones are naked.

Angels speak from their thoughts and have “thoughtful speech” or “audible thought,” although they can’t pronounce any human language. They speak using spiritual air. But angels do have books, and the naked, childlike angels of the inmost heaven have eerie written materials, recording a high purity of thought, which contain nothing but numbers arranged in patterns and series. Swedenborg explains: “Numbers represent general entities and words specific ones. Since one general entity involves countless specific ones, numeric writing enfolds more mysteries than alphabetic writing does.”

In heaven, husband and wife are joined into one mind; they become not two angels but just one. In hell, couples live together out of lust but “burn with a mutual hatred so murderous as to be beyond description.” Swedenborg wondered whether children, and child angels, were free from evil—but no. The angels informed him that children are nothing but evil. But to be fair, so are adults, as long as we love ourselves more than we love God. As Swedenborg put it, “Our world’s sun means self-love.”

It is not possible in heaven to have a face that differs from our feelings. In the afterlife you get the face you deserve—the face of your inner person. During life you also had an outer person. The outer person is structured like earth, the inner like heaven.

Heaven itself is structured like a vast human. The highest heaven forms the head, the middle heaven the torso, the lowest the feet and fingers. “People who are in the eyes are in understanding; people who are in the ears are in attentiveness and obedience; people who are in the nostrils are in perception; people in the mouth and tongue are in conversing from discernment and perception.” Even the “tiny organelles and viscera,” the “individual vessels and fibers” show a correspondence between heaven and human. But the most active power belongs to the angels of the arm in the universal human, and once Swedenborg saw a bare arm appear in heaven that could have crushed his bones to powder.

As heaven is shaped like a single angel, so hell is shaped like a single devil. The hellish spirits inside look like savage monsters, but God has mercifully made them look human to one another. God, ever gentle, never sends anyone to Hell; the corrupted spirits cast themselves in. “One man screamed aloud in utter torment at a breath of air from heaven, but was calm and happy when a breath from hell reached him.” Since spirits after death become their overriding passions, their hells represent total immersion in their ways. Therefore, evil people disappear into murky cellars. Plotters move in dark rooms and whisper in corners. Pedantic academics dwell in desiccated areas. Hypocritical churchgoers settle in stony areas and rock piles. The egotistical study magic. Misers live in filthy cubicles filled with their foul breath. Slippery people who misinterpret truths to serve themselves end up loving urinary things. Devotees to pleasure wallow in feces and latrines. Adulterers end up in brothels, he says—and seems to consider them punished.

In the spiritual world, there are hells everywhere, under mountains, plains, valleys. Just check the fissures in rocks: inside you’ll see the burnt ruins of cities, or crude huts where hellish spirits quarrel violently. These scenes will be lit as if by embers, but hell’s light turns to darkness if ever touched by light from heaven.

The hells are governed by angels who rein in the demented mobs, for the denizens of hell can be controlled only through fear of punishment. There is no other way.

Swedenborg reckons that the universe has one million planets. Each has three hundred million humans. Every planet has humans. God created the universe only to make the human race and a heaven, “for the human race is the seedbed of heaven.”

To us, God appears in two places: one for the right eye and one for the left. In the right eye he looks like our world’s sun. In the left eye he looks like a sparkling moon surrounded by many sparkling moonlets. He appears this way because some people accept him through love, which is fire, and some through faith, which is light. Swedenborg himself saw heaven through a covering within his body rolled back by angels, a strip that extended from his left eye toward the center of the nose. He saw a color like the one we see through our eyelids. Then something was rolled gently off his face, and he had “spiritual thought.”

The Last Judgment is over. Yup: in 1757 the Last Judgment was completed—in the world of spirits, where all must pass on their way to heaven or hell. If you ask me, I think we should feel relieved. The Judgment has come; the world has already ended. The world ended before we were ever born.

The raving goddess, Kircher’s polychromatic angel, and Lautréamont’s cannibal god

Nietzsche observed that every philosophy is a “confession on the part of its author and a kind of involuntary and unconscious memoir” (tr. Hollingdale). We look at the world through self-colored specs; our highest ideas, seemingly made of refined reason, sprouted from a swamp of emotions and were pruned by the scissors of moralities learned at knee height. Reading Swedenborg, readers hear that even heaven has rich people and poor. “Rich” apparently means “spiritually wise,” but he also says:

There is no need to give to the poor except as there spirit moves us … As long as there is an inward acknowledgment of the Deity and an intent to serve our neighbor, we can become rich, dine sumptuously, live and dress as elegantly as befits our station and office, enjoy pleasures and amusement, and meet our worldly obligations for the sake of our position and of our business and of the life of both mind and body.

With all proper respect to the baron, his ruffled rump, cushioned on its feathered pillow, is showing. He had his vision, but he didn’t see himself. That’s the thing about involuntary visionaries, the victims of divine visitations—they’re unlikely to deconstruct themselves or their world all that far. Instead they modify or embroider what they’ve already been taught, and really they’re fortunate if after chumming with the divine they can do anything but babble and howl. They are at the mercy of hallucinations. Swedenborg, with his Enlightenment Protestant mind of scales and balances, put a well-powdered face on his madness, yet he was just a new-generation participant in a great tradition of celestial lunacy which stretched back into prehistory, to the Mystery cults and probably the roots of all religions.

However, Swedenborg was equipped with the reassuring sword of contemporary reason; the antique cultists had no such hale-and-hearty aplomb in the face of the divine. They found it more reasonable to go insane upon being visited by the divine. More than one god seemed to make an identity out of driving us into frenzies. In The Orphic Hymns (covered in Issue #3), Athanassakis and Wolkow write of Kybele, Mother of the Gods, who “raves and is able to send madness to those she chooses,” that

Wild music and dancing, ecstatic possession and ritual madness … were all characteristic of her cult. … Pindar imagines ecstatic worship of Dionysos celebrated by the gods: Kybele leads off with the beating of drums amid castanets, torches, and the wild shrieks of Naiads … The power of the goddess’ madness reaches its gory peak in the self-castration of particularly dedicated male worshippers.

Kybele, spare me! AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAHHHHH—

Encountering the divine is always a risky endeavor; one can never be certain how one stands in the eyes of such beings. Contact with the more-than-human carries with it the danger of losing one’s speech, one’s senses, even one’s sanity. This concern is reflected throughout the collection in that many of the hymns either explicitly ask that madness be driven away or implicitly do so by requesting the divinity addressed to come with a peaceful disposition. Comparable is the petition at the end of the hymn to Dream that requests ‘do not through weird apparitions show me evil signs.’

Nice try, but the weird apparitions often come loaded to the fucking gills with evil signs, and even the angels can bring a goodness so fiery that it scorches away your bones. And if you are an involuntary visionary, they come when they bloody well want to. Maybe you chased them, maybe you hid; you can be scholar or cobbler, you can fast or feast, be fun or nun, but one day your eye becomes a window onto God and your mind gets crammed with alien data. Now reality is a trick, every rock a flux, and every note you jot turns up impossible palaces, nested worlds, heaven and hell as twin mirrors. And even if you’re lucky enough not to descend into total schizophrenia, even if you’re a scientist scribe of angels, at best you receive just one special metaphysical blueprint—perhaps with later revisions and alterations, but always bound to your closed set of received ideas. The theophanic vision is almost always like a mazy orchid sprung up on the mossbound trunk of mainstream religion: it is helpless; it cannot sprout elsewhere; it must live out its life on that branch.

Involuntary, unselfaware visionaries have their place in history. They can found religions, uplift or destroy generation after generation of future people, inspire academic study and practical action, provide writers with characters or settings or even render up vivid collectibles for this online bodega of bizarreries. The Orphics left only a collective trace, but a powerfully strange one, and Swedenborg was an impressive constructor, even if all his cosmic architecture was built under a sheltering leaf of Protestantism.

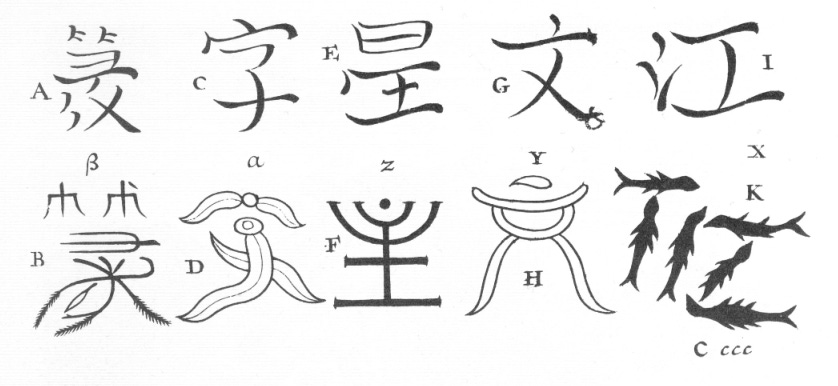

But that angel-addled aristocrat created on a leash. It might be instructive to compare him to the exuberant and indefatigable polymath, Athanasius Kircher. Frequently billed as The Last Man Who Knew Everything, Kircher was famous in his lifetime for many major works of theology and science, popular illustrated books, and other, more checkered intellectual projects—such as the first Western study of Chinese characters—that were totally wrong in the most creative and interesting ways.

Writing a few decades before Swedenborg was born, in a text called Ecstatic Itinerary, Kircher describes a polychromatic seraph called Cosmiel, who takes him on a cosmic journey through the solar system to explain modern ideas from the astronomical sciences. To be sure, Kircher also prostrates himself before God and Christianity, but he has constructed Cosmiel as surely as an inventor his robot. His writing is art:

In this state of slumber, I found myself within the boundless expanse of a meadow, and before me stood an extraordinary figure. His head and countenance were adorned with a mane of otherworldly splendor, his eyes gleamed like precious gems, and his attire was unlike anything I had ever seen. Notably, his wings were intricately folded, displaying feathers of almost infinite hues. His hands and feet radiated a brilliance surpassing that of any precious stone. In his right hand, he held a sphere adorned with representations of the orbits of wandering stars, each depicted as diverse-colored gem-like spheres—an awe-inspiring sight. In his left hand, he held a finely crafted measuring rod, a testament to his unparalleled artistry. Overwhelmed with awe, my heart raced, and every fiber of my being quivered, leaving me scarcely able to draw breath, let alone form words. Within this surreal setting, I heard a voice—more melodious and enchanting than words can convey—resonating with profound significance… [Translator unknown]

But Kircher was still pious, his books published with the imprimatur of the Vatican. As the status of humans was hoisted through Renaissance to Romanticism to Realism, there appeared ever more sophisticated, ironized visionaries and angel-makers, artful dodgers who shrugged off God and usurped power. These latterday kickboots didn’t suffer even the divine to lord it over them, casting off the weight of the ages without needing to commit fully to their own proposals. Speculation was the rule, subjectivity truth. In the 19th century, Comte de Lautréamont—a French student, Surrealist avant-lettre, goth-Romantic hurtboy whose real name was Isidore Ducasse—flourished into his “somber and poison-filled pages” a voluntary vision which might make one wish God was dead. From a translation by Paul Knight:

I lifted my eyes higher, and higher still, until I saw a throne made of human excrement and gold, on which was sitting—with idiotic pride, his body draped in a shroud of unwashed hospital linen—he who calls himself the Creator! He was holding in his hand the rotten body of a dead man, carrying it in turn from his eyes to his nose and from his nose to his mouth; and once it reached his mouth, one can guess what he did with it. His feet were dipped in a huge pool of boiling blood, on the surface of which two or three cautious heads would suddenly rise up like tapeworms in a chamber-pot, and as suddenly submerge again … until, finding his hands empty, the Creator, with the first two claws of his foot, would grab another diver by the neck, as if with pincers, and lift him into the air, out of the reddish slime, delicious sauce. And this one was treated in the same way as his predecessor. First he ate his head, then his legs and arms, and, last of all the trunk, until there was nothing left; for he crunched the bones as well. And so it continues, for all the hours of his eternity. Sometimes, he would shout: 'I have created you, so I have the right to do whatever I like to you. You have done nothing to me, I do not deny it. I am making you suffer for my own pleasure.' And he would continue his savage meal, moving his lower jaw, which in turn moved his brain-bespattered beard.

But this spitting and snarling at a sadistic God could come only from a man embittered by Christianity; he displays all the symptoms of an animal tormented by thorns. Because Lautréamont didn’t step far enough back, he could not represent the height of the voluntary visionary—the metavisionary.

With that term, I don’t mean the usual presidents, plutocrats, and pop cats who get called visionaries. I mean a rarer type, a modern-style figure who emerged only after centuries of our slow struggle out of the christ glue of the Middle Ages, becoming possible as the human clambered up over God. I mean someone who attempts to fill the higher-dimensional hole left by God’s death, using all the mental tools that once belonged to religion. The metavisionary bridges the god gap by taking up the meaning-making apparatus from religion and turning it into a pageant within the consciousness, trafficking in gods, symbols and archetypes, weird metaphysics, the ineffable, speculations about the universe and existence and consciousness—yet always standing outside the religious systems. Leashing them to life. Making mythology a story of the self.

Such a figure could come to fruition only in a more globalized, translated, relativized world, where so many theses and theologies, stories and speculations are available for near-instant consultation. There’s something to be found in the mythology and madness of every age, some concept always threatening to be lost which should be recovered and assimilated into the fresher waves of the human imagination—but the modern mind no longer needs to pick a side and stick to tradition. You don’t need to toss on a bed of nails, or listen only to angels, or spray graffiti on the Tetragrammaton. Your philosophy, rather than being an unconscious memoir, can be a conscious celebration of everything you want to create in yourself. You can become a constructor of visions, a top-down architect of the cosmos. Not commanded by the angels, but commanding the angels, making heaven after heaven, hell after hell. You could become someone like the warlock of Northampton, Alan Moore.

Alan Moore and Promethea

Alan Moore is best known for creating some of the most original, profound, and influential comics of all time, as well as for deconstructing many existent superheroes, more often than not writing the most memorable story in each hero’s history.

Notoriously, he’s also a ceremonial magician, a wizard-bearded and beringed anarchist who worships an ancient Roman snake god called Glycon—whom Moore admits was the blond-wigged puppet of an itinerant conman. How can Moore worship a god he admits doesn’t exist? Well, to understand what he’s on about, the quickest way would be either to pick up his co-written primer on the occult, The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, or to read his occult comic Promethea, a magical mystery tour and resplendent visual spell meant to cast an enchantment upon its readers.

But Moore’s occultism and his achievements in comics are of one piece, a unified metavision, and before I start on Promethea I’d better riff a bit on his other writing.

I’ll be frank, though. I do not give a shit about superheroes. When Moore writes them, though, he does so with a psychological complexity, existential eloquence, linguistic ornamentation, and formal inventiveness all at levels rarely seen in prose, let alone comics, and all integrated by a highly sophisticated talent for multilayered storytelling. His tightest work is Newtonian, architectural, and fractal, each issue not just a tightly paced story crammed with ideas, plot, suspense, and memorable characterization, but also a gear turning smoothly and symmetrically within the narrative’s masterfully constructed system of meaning. Would I be pushing your patience if I described the effect as a cuckoo-clock funfair backturning tour with a gem-fingered magus grinning out from its cogwheels? Or no, that image doesn’t suffice either—it doesn’t get at the fact that he’s always writing about what it means to be alive, to be human with a mind, and to have to love one another.

And his major works don’t just succeed as self-contained stories, but as big conceptual statements where he attempted to push the genre into new territory. From the ‘80s to the ‘00s, he must have asked just about every hard question one could ask of superheroes, expanding the genre with the exhaustive program of an era-defining genius. Before Moore, superhero stories almost always depicted shining idols fighting against entrepreneurial evildoers or foreign fascists; the literary critic Northrop Frye would not have hesitated to classify such tales as naïve melodrama, which (1) defines the enemy of society as a person outside that society, (2) seeks the triumph of moral virtue over villainy, and (3) idealizes the moral views of the audience. Such melodrama isn’t just naïve: it’s empty, lopsided, and boring. It’s propaganda. Someone had to make the genre grow up and get a real theme.

So, what if an all-too-human hero took on the fascist government in his homeland? What if that nation was clearly modeled on contemporary Britain? And what if the hero was an anarchist with no love wasted on any state?—Then you get V for Vendetta.

Conversely, how would an omnipotent superhuman use his powers? Would he really just scoot around walloping dudes? Wouldn’t it make more sense for that supreme being to take all human destiny under his tutelage? What if, bestriding the planet like a unitarded colossus, he toppled the world’s governments and instituted a “utopia” that permanently limited all human freedom?—these questions yielded Miracleman.

Or what if the superhumans are screwed-up, corrupt, hopelessly imperfect, even impotent in bed, and what weird plan might such an ambiguous elite, from their monstrous vantage point, agree upon to save humans from themselves? And what if that plan entailed a utilitarian hecatomb of innocent life?—and here’s Watchmen.

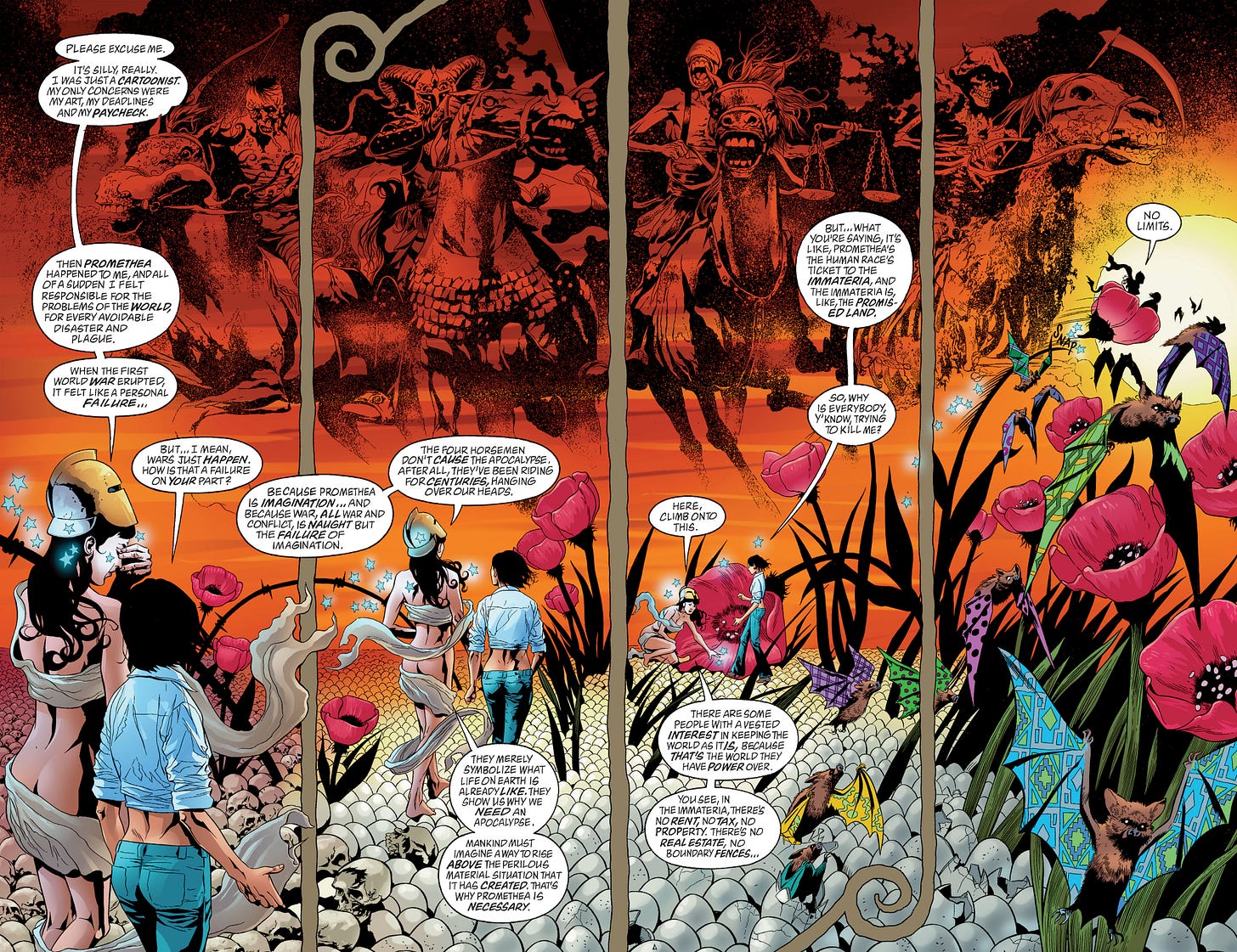

Sharp, unsentimental about human shortcomings, imaginative but ultimately kind of depressing, right? After reaching this nadir of dismal darkness, and having already ushered in an epoch of copycat doom’n’gloom heroes by writers with rather less than half his talent, Moore reversed course and tried to restore superheroes to their playfulness and innocence. Comics like Tom Strong, Supreme, and Top Ten were all roguish meta reconstructions of superhero tropes, nostalgic romps with a presiding spirit of vibrant unreality, healthy fun, and intellectual exploration, done in burlesque dialogue and samite prose. Comics about comics, with ideas about ideas.

But these tropes only had so much mileage, and Moore finally seemed to ask: what about an actual superhero? She couldn’t be a deconstructed figure of fun, nor a person who manipulates the public with infantilizing lies, no dictator or daily socker of jaws. A real superhero wouldn’t save just bodies: bodies are only the brute basis of higher life. A real superhero would save minds. She would wake people up, help them become better versions of themselves, and inspire them to build a new world. All superheroes come from the imagination, but she would be the first superhero of the imagination, of individual self-actualization, with the power to turn others into heroes. And if she was written well enough, she might even spiral out of the page and transform the reader too.

And what else could you call this transcendental superheroine and benevolent purveyor of divine fire, except Promethea?

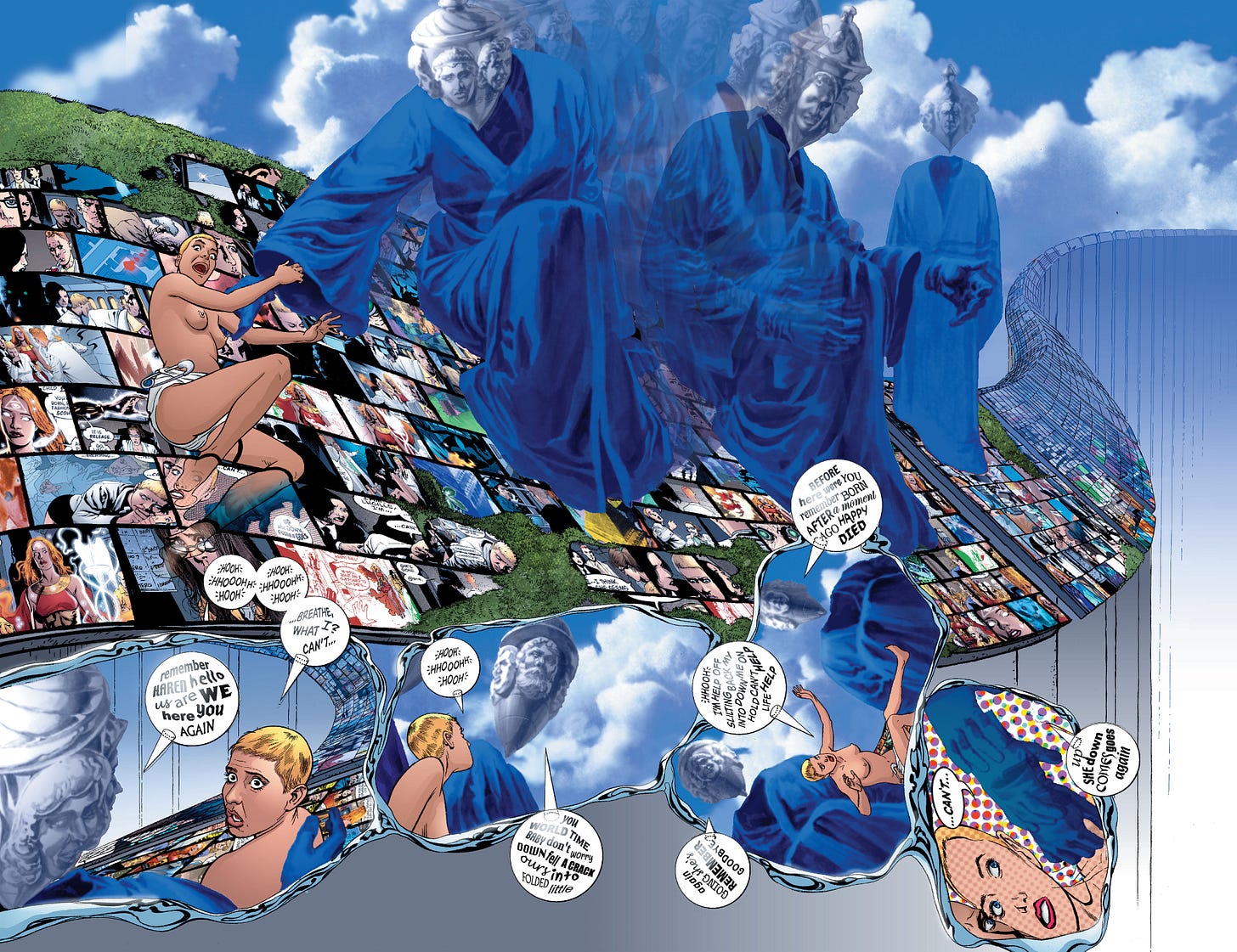

The story opens in fifth-century Egypt. A posse of Christians bearing spears march through dusty streets, heading for the home of a pagan magician. The magician confronts them and dies impaled on their spears, but first he sends his child daughter Promethea into the desert, where she’s taken up by the composite god Thoth-Hermes and brought to a place called the Immateria.

The Immateria is an intangible ideaspace where everything is concept, archetype, belief, fear, dream. Upon entering it, Promethea leaves behind her flesh and becomes an idea, a sort of recurring story, like the gods, angels or spirits, or like popular heroes or villains, or characters from fiction or history—all the mythical, legendary, or otherwise memed personalities who haunt the collective imagination and exist beyond the mind of any single person. As an idea, Promethea is deathless, and over the millennia she descends many times to our plane of reality and merges with mortals whom she’s been summoned into by an act of imagination. Her numerous vessels have never used her powers to the fullest extent, but as the story begins, Promethea is about to merge with a young girl who will bring about the apocalypse.

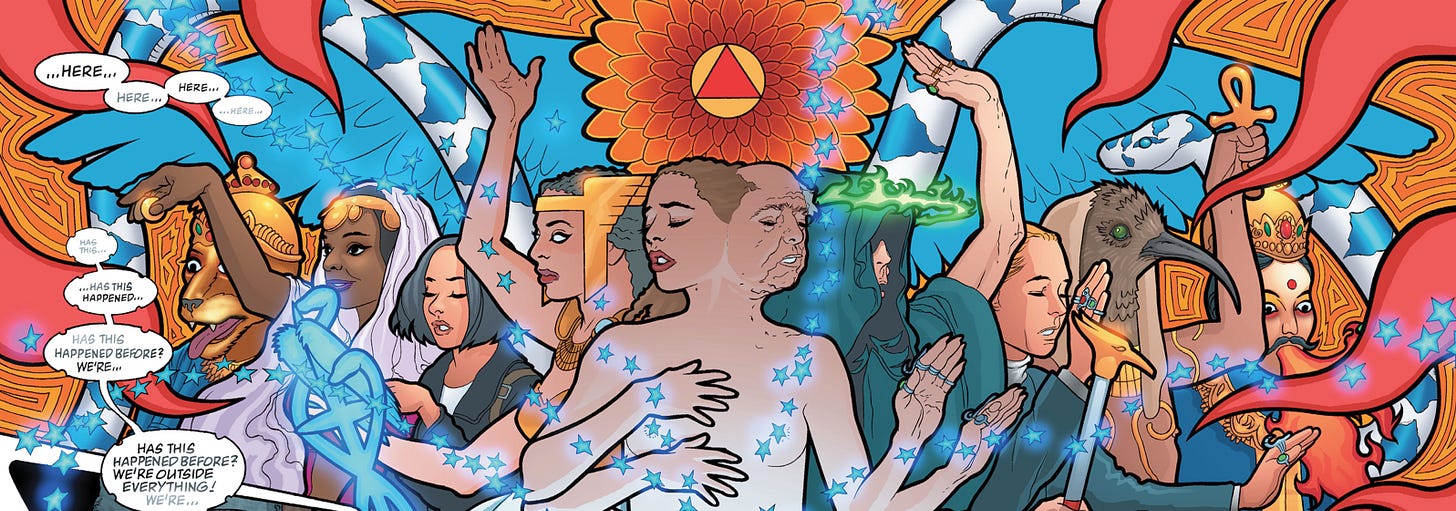

The first arc follows the newest Promethea as she begins to accept her role. There is an ominous cabal and a demon siege, a brassy friend, a lascivious magician, a trip to the Immateria, and many other threads of story, idea, and symbol, but despite the overall structure being a classic Moore tapestry where every element gets woven in symphonically, it soon becomes apparent that the comic’s plot is only the supporting rail for a headbending ride through a Crowley-derived funhouse of occultism. The story gets psychedelic real quick, for instance in the showstopping Tantric Sex lecture where the climax involves both parties pulling Kundalini energy up their spines, fusing and bursting into the rotating faces of many gods, aspects, selves.

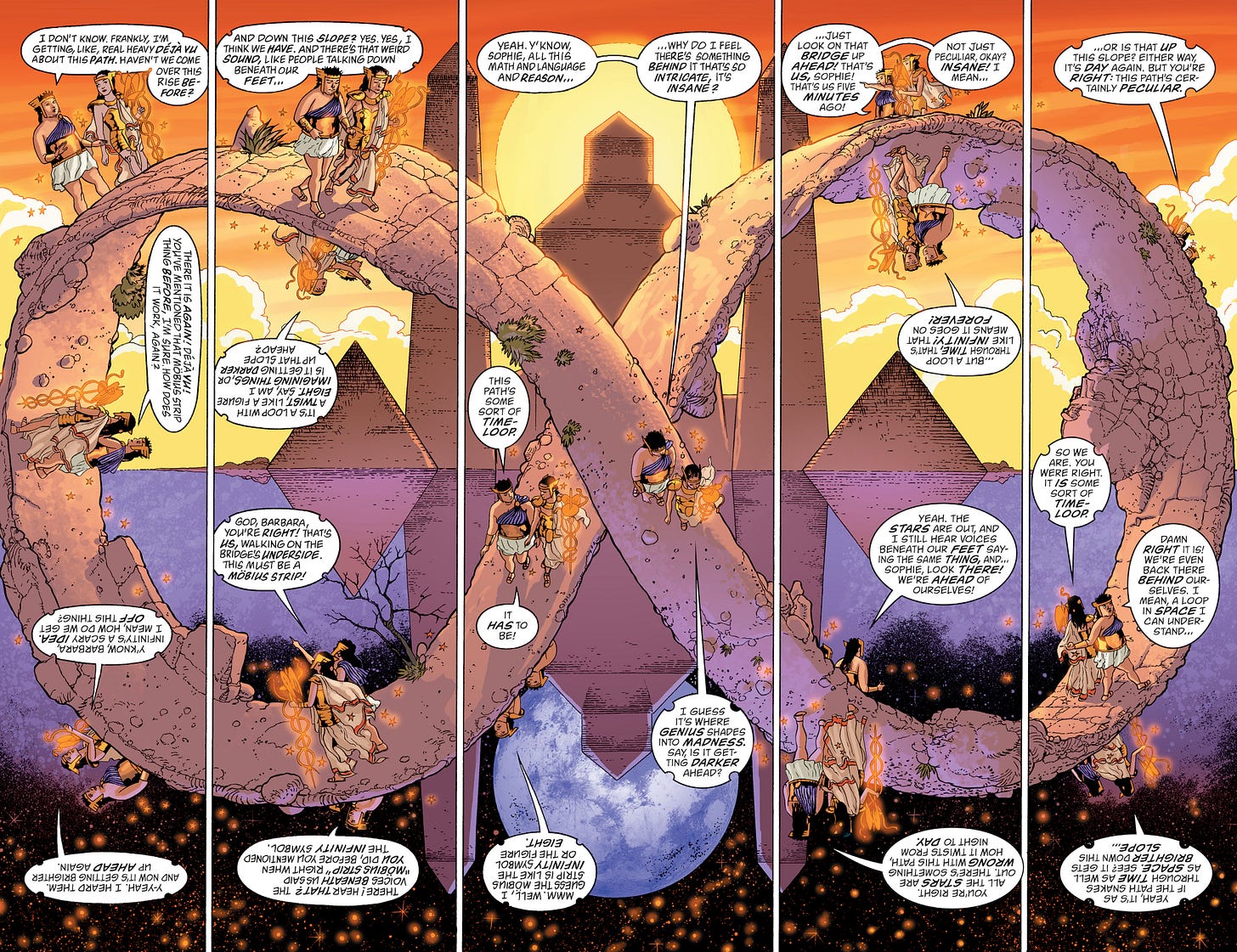

As the first arc closes, the new Promethea realizes that to understand her duties on Earth, she must travel up into the Immateria and beyond, to the surreal and mystical heights above our universe. She will have to ascend the Tree of Life—which is not a literal tree, but a knotted cosmic architecture that relates the earthly to the eternal.

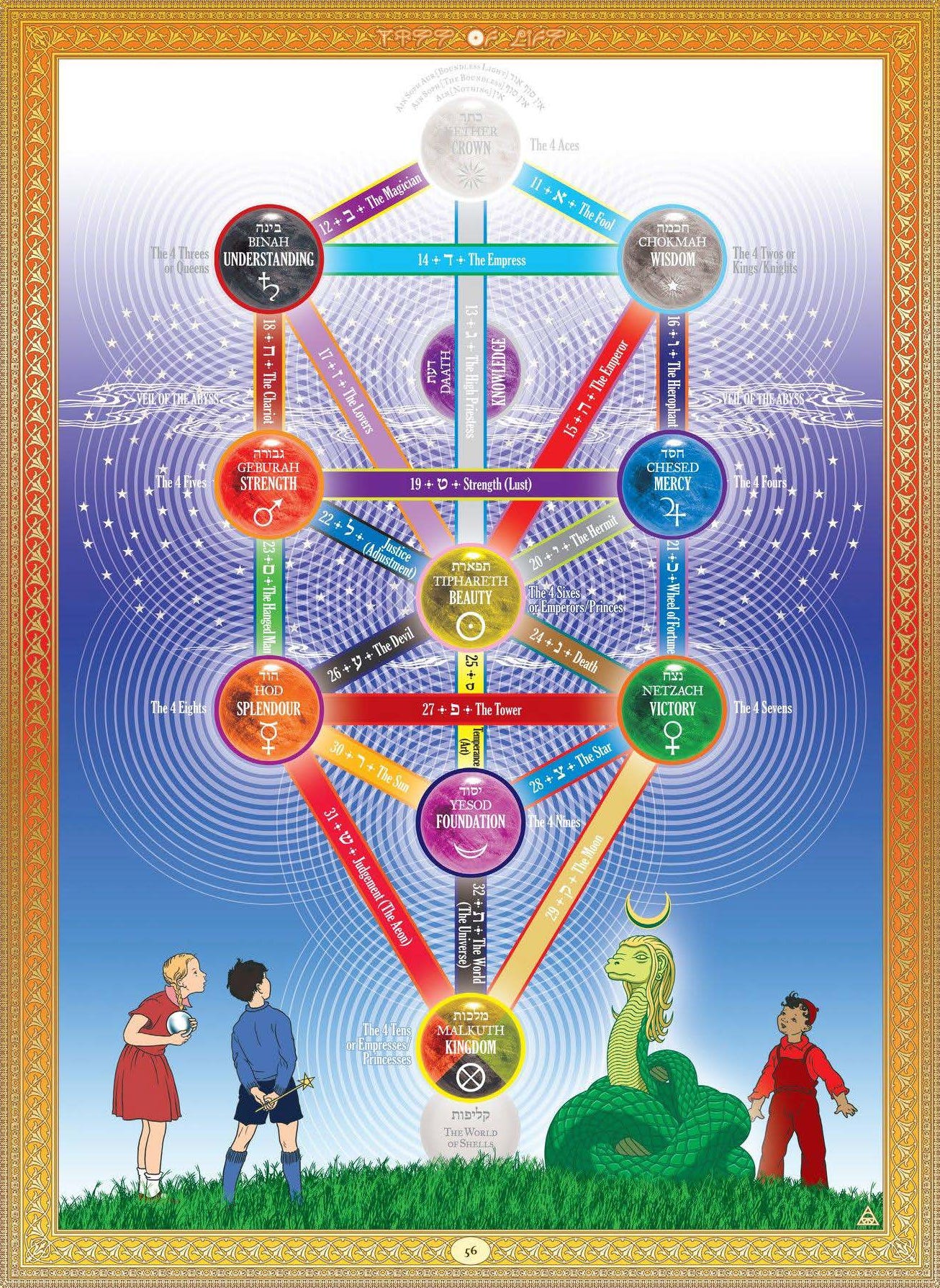

The Tree of Life or Sephiroth, a venerable concept from Kabbalism that fuses Judaism with Neoplatonism, represents the attributes or emanations of God as ten descending spheres. With each step down from the pure power of the top sphere, which is the Godhead, divinity becomes more imperfect and fragmentary but also richer and more complex, terminating in the blistering diversity of the bottom sphere, which is our reality. Over the millennia, occultists of all stripes have embroidered much on the original concepts, associating the separate spheres with deities, archetypes, imagery, animals, perfumes, and interrelations, until the Tree of Life, draped with metaphysical jewelry from a myriad of world religions and traditions, became a magical switchboard for a crossconnected multitude of occult notions, a conceptual tree-metropolis imagined in dizzying detail, meant to map not just the cosmos but the soul.

As Promethea climbs the Tree, she passes through ten intricate ideascapes, each filigreed with associations that converge on an aspect of God or mind. In ascending order, these ten spheres or places are (to put it very roughly) Reality, Imagination, Intellect, Emotion, Beauty, Strength, Mercy, Understanding, Wisdom, and Godhead. By exploring these ten places, and learning of their gods, archetypes, and roles, the superheroine of imagination confronts facets of her soul and of all humanity, considering how to be, how to act, how to conceive of herself. Gradually she approaches a unified theory of personality, rising toward enlightenment, and along the way each sphere has its own issue done in different art styles by the versatile J.H. Williams, the comic form gets twisted with tireless ingenuity, the deepest questions of internal life are addressed, and there is much many-folded velvety prose in Moore’s warm and generous voice, where elegant profundities jostle against silly jokes and every leap into darkness is counterpoised to a flight of joy.

Finally, after attaining the Godhead and her highest self, Promethea returns to our reality—the bottom sphere—and touches off a psychic Armageddon where everyone on earth is subjected to what is basically the most illuminating acid trip of all time. At its delirious peak she speaks to everybody in a cozy firelit chamber deep in their minds, where she jacks them into eternity and reveals to them the runaway, overwhelming, monumental beauty of the universe and their souls, burning away their materialism and awakening them to the life of the pagan imagination. Emancipated humans bring about a technicolor utopia of the free, the kind, the tuned-in and turned-on, and everyday life becomes tremendous.

Suddenly we were all exactly who we were, for better or worse … and we kept catching ourselves in the mirror, recognizing something, something shining under the familiar crease and contour of our faces, this unique light of our mythical, our holy personalities, each of us singular, each unrepeatable in the immensity of Spacetime and right there we all remembered we were real, were lovers, gods or fiends in our burning sagas so we cried, “What are those dreary yards that we have built? What lives are these that drape us gray like shrouds?” and understood we were all heroes in our souls...

But Promethea stares out of the page, speaking directly into your eyes: the spiral of enlightenment encompasses the reader, too. Neither she nor the inhabitants of her immaterial comic world are the actual audience for this lecture on the occult. That would be you, the reader. In an early chapter, Promethea calls her friend and asks her to step outside a night club; on the wall are several pieces of graffiti, but one sticks out: “Who’s watching you?”—an obvious reference to Moore’s most famous deconstruction of superheroes. Who’s watching you? It’s Promethea calling you away from the party; it’s Moore, and this time he’s deconstructing you. His magic spell is the comic itself, as outlined in the documentary The Mindscape of Alan Moore:

I believe that magic is art, and that art, whether that be music, writing, sculpture, or any other form, is literally magic. Art is, like magic, the science of manipulating symbols, words or images, to achieve changes in consciousness ... Indeed to cast a spell is simply to spell, to manipulate words, to change people's consciousness, and this is why I believe that an artist or writer is the closest thing in the contemporary world to a shaman.

Late in the comic there’s a recurring image of a Wand—which means Will—being plunged into a Cup—which means Emotion or Compassion. The wand into the cup serves as the symbol for performing an act of magic; and during the apocalypse, when everything is hypersymbolic, the onset of superreality gets triggered by a woman dipping a swizzle stick into a tumbler. Now the story’s beginning looks a bit different. Now when the Christian monks ram their spears into Promethea’s father, their spears look like the wand plunging into a cup of blood. Her father, a sort of Muhammed Ali of tactical wizardry, has turned their attack on him into a work of magic setting up the distant apotheosis of Promethea. Look even closer: maned and bearded, he resembles Moore himself, the true “father” of Promethea, who generated the script by dipping his will into his emotion. In fact, in the father’s very first panel, we see him plunge his stylus into a pot of ink, just as Moore and Williams did—stylus into ink, spear into body, wand into cup, swizzle stick into tumbler. The comic’s magic is fractal: it descends from Moore, spirals down through the comic-book world, then sizzles up into the reader reeling from the rainbow pages.

All this may be rather hard to swallow if you distrust Moore, if you can’t forgive the comic its grating imperfections, and especially if you reject the effervescent occult system he offers as an elixir to awaken the imagination.

To the personal objection, I’d encourage hesitant readers, especially those turned off by certain plot elements, to entertain what he’s saying and see what they can glean from it. I, for one, steal from everybody I can. Everyone has at least a shard of some secret; and Moore, as has been demonstrated by the success, influence, and cult of his writing, has rather more shards than most people. It’s true he makes the reader work and can be difficult. It’s true the writing is sometimes dense and you need patience and discernment in order to separate what you accept from what you reject. So?

The objection to the work’s flaws is understandable, I feel. Some sequences and characters are weak or even mildly irritating. There’s a rhyming verse poem on the Tarot that’s a tough slog for me. The post-Promethea utopia is disappointing, too loopy, too soppy, and oddly Fukuyamaish, perhaps indicating the limitations of Moore’s political philosophy. And there’s a significant line about a kiss that lasts forever, which, despite locking cleverly into his theory of eternalism, is wildly, sitcommishly cheesy—particularly since the characters’ relationship is too underdeveloped to carry the sentiment. All too often, a polluting whiff of ‘90s sitcoms clings to Promethea and taints the aroma of its polychrome potpourri.

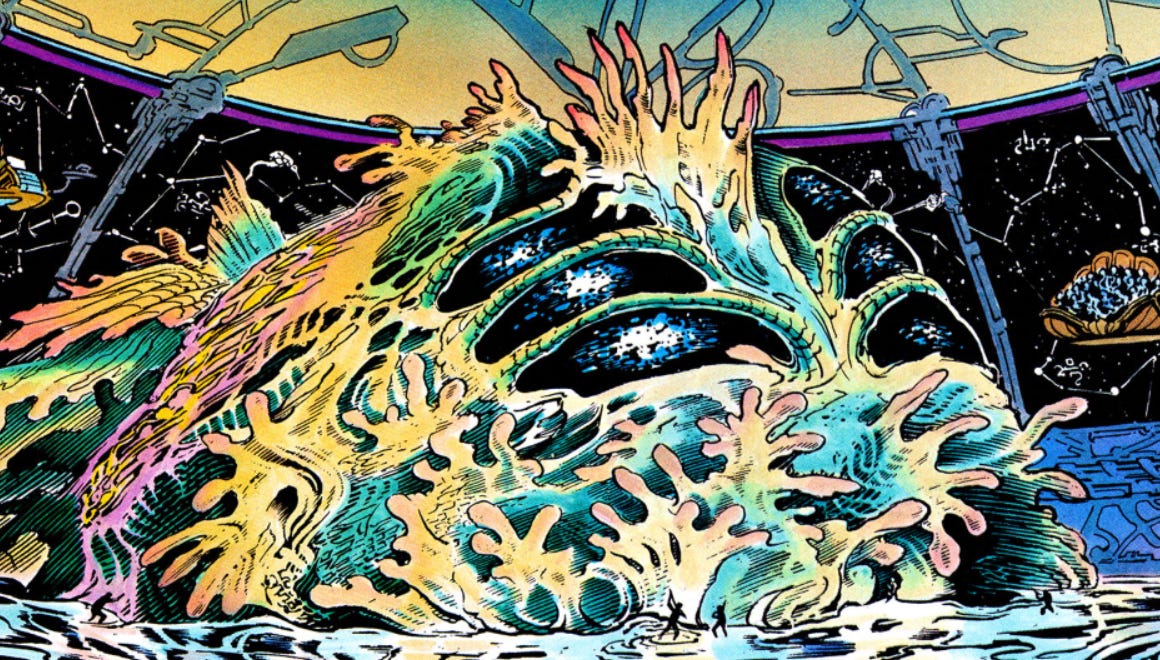

And although Williams did a brilliant job on the art, which is unfailingly well-conceived, some design choices look dated, particularly the photographical sections and some ugly computer art with artificial gloss. Maybe I’m just personally biased against synthetic colors, but I much prefer the incandescent hand-inks of Miracleman:

But really, I’m just listing these potential blemishes so that readers won’t get discouraged. Moore, in crafting an action textbook, couldn’t hit the story highs of his best-told titles, since he had to balance the development of character against the conveying of information. For someone staging a philosophy lecture, he did remarkably well at varying the flow, putting characters through changes, and setting up the climactic showdown. And sure, sometimes the story is sentimental, but bear in mind it’s easier to write critically of pride and cruelty than to write approvingly of love, kindness, and belief. Look past the comic’s superficial imperfections to the gleaming elegance of its conception, and you’ll find his architectonics are more on display than ever, the number of moving parts he keeps in motion is dazzling, and there’s just a lot of lovely, moving, and expressive writing about being a mind in time. For the willing, Promethea has oodles of beauty.

The most serious objection is to the occultism. I get it; I objected too. In my experience, occultists are generally charlatans or insane or some fascinating mixture of both. Prod a believer in magic and often you’ll get goosegabble not just about astrology or gods, but the Freemasons and Templars, Atlantis and telluric aliens and whatever other dubious claims taken from swindlers squeezing the gullible for a buck. I myself am a stubborn skeptic of the supernatural, a nonbeliever who writes about wizards with amused fond indulgence for their character, with love for their writing and imagination, and with comradely respect for their oddball, self-willed lifestyles—never with belief. I can well understand why for many readers Promethea might seem like the Wonderwoman of Woo, Alchemical Anarchistical Athena.

But Moore’s up to something subtler. Here it might be useful to recall that he worships the snake god Glycon. Remember Glycon was a puppet, a hoax from a false prophet, and Moore cheerfully admits Glycon was a con. So… why worship him?

Moore can be cagey about what kind of existence he thinks gods have; it’s enough that they exist in your mind, he says. Whatever you think of their reality, you do think of them, the gods and legends live in your head too, and they have shaped billions of brains and inspired world-altering actions. People kill and die and live for deities, and they model themselves on myths, heroes, and stories. Fictional characters spawn real-life imitators, children sitting in cinemas enthralled as their new personality struts across the screen—sounds silly, until the child bases their future on that frisson. Once upon a time, Moore too sat at his desk and dreamed himself a career in the arts. The imagination changes reality without ever needing to manifest literally.

And this is particularly true when it comes to consciousness. We assume we live in reality, but it’s more that we live in our ideas about reality. Physical existence is only an anchor, a starting point for what the mind makes out of it, whether trash or treasure, tragedy or travesty. A meat-eater sees a tasty treat; a vegan sees murder most foul. The blessed weep; the afflicted laugh; the maimed may caper as the young, rich, and beautiful slit their wrists.

So, Glycon’s reality is beside the point. Or his unreality is part of the point, since he is blatantly what all gods are secretly: a construct of the imagination. No matter what ceremonies Moore performs or what psychedelics he ingests, he can always slip the blond-wigged snake back into its crate. All the same, the snake-god still serves as a focus for mental energy, as an active imaginative conduit to worlds above and within. To worship Glycon, Moore had to make an altar and four magical artifacts, to write invocations and carry out rituals, in other words to concentrate his imagination on a large and visible project whose result would protrude into his daily life. Now the fair-haired serpent coils on its altar, dredged up from the swamp of dead notions into the private world of his home, where it functions as a handcrafted skeleton-key dream for the locked gate of the occult. Unreal, maybe—but existent enough to have a permanent presence in its creator’s life. And at least as real as any idea.

So Moore’s argument goes. By this same logic, climbing the Tree of Life can be an exercise or serious game for nonbelievers. Treat it as an elaborate lattice for the mind to climb like a trellis, twining up in search of adventures for the dreaming self, for new possibilities in creativity, self-conception, consciousness. A bit like a fictional world, except the main character is you exploring underdeveloped parts of yourself. In Promethea he visualizes the ten spheres or places as a metro system for mental exploration—more properly named, they are Crown, Wisdom, Understanding, Mercy, Strength, Beauty, Victory, Splendor, Foundation, and Kingdom, and the twenty-two paths linking them have been made to correspond to the Tarot’s twenty-two major arcana (that is, the Lovers, the Hierophant, and so on). Meaning that as the meditating mind moves from one sphere to another, the imaginative connection has been enriched by the Tarot cards, which themselves, following Crowley’s Book of Thoth, have been festooned, rhinestoned, and bewinged with concepts out of alchemy, mythology, Christianity and Judaism and and and and—all interpreted as movements within the mind, gods and legends and heroes spinning on a merry carousel of archetypes inside the self, blending as they rise into the blinding light of the Head.

Nor does Tarot need to predict the future. It can be subtilized into a technology of self-interpretation which uses chance to suggest new perspectives. Its four suits—Swords, Wands, Cups, and Disks—have been made to represent Intellect, Will, Compassion, and earthly needs, seen as the four aspects of existence that humans should tend in themselves (not bad advice, by the way). Each suit has ten cards, and they’ve been paired with the ten spheres of the Sephiroth and given Kabbalistic analyses. Take for example the Eight of Wands. Wands mean Will, so the card is Will interpreted through the eighth sphere, Splendor, that is, Reason, Intellect, or Language. In The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, Moore and co-author Steve Moore say: “The Eight of Wands, Swiftness, finds the powerful suit remedying some of the deficiencies of the eighth sphere, manifesting as fiery Will in an ideal setting of intelligence and communication, able to act quickly and efficiently.” By contrast, combining the suit of Swords and the ninth sphere would cross the meanings of Intellect and Imagination: “The Nine of Swords, Cruelty, is a most unfortunate card illustrating the painful disillusion that comes when a long-treasured dream is shattered by its exposure to intelligent waking reason.” Moore would say these are useful lens to evaluate situations in our life; might they indicate a course of action?

There follow another thirty-eight cards with similar interpretations, plus the court cards and major arcana. In this rationalized form, Tarot functions as a symbolic barrage, a charm to change your mind. You ask it a question, shuffle the deck, and let it spread suggestions before you, its cards like tickets to ideaspace. As you muse, grinding wheels of symbolism align their icons as if in a magical slot machine where every combination is potentially fruitful; the Tree of Life lights up like a Christmas pine; and pantheons and bestiaries flutter wings, mythological characters leaning in to add their slants to the potential interpretations, their ornate presences investing ordinary life with the archetypal grandeur of the oldest stories. As above, so within.

This stack of occult devices reminds me of an electronic musician’s set-up, with instruments, pedals, synthesizers, and processors interlaced by a spaghetti of colored wires. It is the occult as a plexus of imaginative technologies meant to transform consciousness through the concentration of mental energy and the concerted manipulation of symbols. The occult as a way of thinking. As art, not science. Creativity, not truth. After the ritual’s sounds and lights subside, the snake, should it refuse to stop moving, can be stuffed back into its crate.

Is Moore’s occultism really as secular as I’ve laid out? Not always—although especially in The Moon and Serpent book it’s hard to be sure which opinions come from him and which from his co-author. Mostly he seems not to believe in life after death, but he does believe in eternalism, which posits that every moment exists in eternity and our lives are only a lower-dimensional movement through a static higher-dimensional structure. Apparently Einstein thought so too; I don’t know what’s correct, but eternalism is anyway an artistically fruitful idea. Finally, Moore does believe in the Immateria or Realm of Archetypes as an autonomous zone in a way rather less metaphorical than I’m willing to defend. I’m sure I’m more skeptical than he is. At least, gone or ironized in his work are the trismegistic fraternities dispensing secrets and hard-reversing the scientific perspective; emphasized instead are the loner visionaries, studious raconteurs of the infinite, who pore over weird tomes and amass exotic imaginaria, worshipping the mind at altars to art.

So, am I endorsing this version of the occult? As a thought experiment, in which the merely psychological reality of the imaginative space is kept firmly within one’s lens, I don’t see why not. I’ve been playing with it and enjoying myself immensely. But rather than having any profound interest in Kabbalah or Tarot, I’m interested mainly in Moore’s metavision—in the stance he takes and the needs he addresses.

Put it this way. Astrology is not true. The stars don’t care about us. Nonetheless, relating yourself to the universe, through stars and planets and animals, is enchanting. It invests relationships with meaning, makes the mundane sparkle, and is more harmless, more universalist than many other symbolic orders within which people situate themselves—say, nation or church, race or team or bling. Nobody murders for their starsign. Historically speaking, other signs have been way less safe.

And we seem to need symbols and stories, to rely on them on an almost neurological level when we interpret our experience. Cause and effect, conflict and resolution: everything we perceive knits into narratives. Without even trying, we continue the patterns we know, often regardless of whether they torment or ennoble, imprison or liberate, guide or blind us. We imagine getting off work; we imagine what we’ll make for dinner; we imagine what an irate neighbor will say; we imagine what our partner would say if we proposed or if we left them; we imagine who we are, or could be, or have been, that we are saved or damned, preserved or obliterated. In midfall we imagine hitting the ground. In the middle of love we imagine loss. Wading waist-deep through the present, we twist to follow our fiction of the future. Everyone envisions the greener grass, the patches of sky through dark forest, even when we feel our lives surrounded by evil and the distance to bliss unsurmountable. Stories within stories within stories: that’s the human rendition. It stops only with death.

The difference lies in what drives each imagination—is it the stars in the sky, the stars on the screen, the stars in the past or the stars in someone’s eyes? Or is the inverse, is it the dark star of hell or death? And why? What do you imagine, what story do you tell yourself, and what do you want from it? Sagittarius or antinomian, why do you believe what you believe and need what you need? And was it really your own idea?

From the beginning we are instructed in what we should imagine, given stories by which to interpret ourselves. The real is policed by people who want to shape us for their ends, which nowadays happen to be primarily secular. Religion used to explain life and lend it brilliance; now the hole it left has been filled with nations, jobs, brands, parties, cultural types, all those secondhand identities that flatten the soul, while the topics that religion addressed—how to live, the meaning of life, our purpose in the world—get discussed only in unsatisfying ways, assigned natural or economic or social or scientific answers that don’t stoke the imagination the same. You can contemplate theories of evolution or the Big Bang in awe, but they don’t write your personal life in letters of fire. Religion was so convincing, and remains such a formidable force, because it is an ark of stories, moody torchlight legendry that swathes the listener in stars. An Indra’s net of symbols, with the Zodiac as baldric.

So, some nonbelievers say we need religion. Man wants to be devoted, they say. Yet there’s a problem for them: religion isn’t true, nor with good conscience can they pretend it is. Worse, it comes with metaphysics and moralities that infect the believer and leave behind thorns even if the belief itself is discarded or modified. Consider Swedenborg: he had original visions, he met angels, but he was stuck within the paradigm of his childhood indoctrination. He may have altered a couple details, toggled a few truths, yet the morality remained bog-standard Christianity. Bound, subjected, profoundly unfree, fixated on guilt and sin, Baron Swedenborg stands in for everyone raised under a system that defines the good, diminishes individuals and demands universal submission. He never did swap his crown of thorns for a garland of flowers. He couldn’t. His mind was manacled by adamantine narratives.

Now consider Moore. Long before he declared himself a magician, he came up as a writer reimagining characters, eventually putting together series where he appropriated hundreds of figures from history, fiction, and myth. Stepping into the world of ideas, he looked around and decided to turn it all to his own ends, monkeying with and reangling whatever he pleased. The vigorous repurposing of concepts under a bold master plan marked out his writing long before it surfaced as the fundamental principle of his magic practice; it’s just that applying the same logic to magic, to his own mind, got him someplace even more empowering and mentally adventurous.

When the vision is created by discipline, study, and strenuous acts of creation, and psychologized as an internal phantasmagoria, it becomes a metavision, a chimera half art and half religion and all self-aware imagination. The metavisionary masters their emotions, keeps belief on a leash, and engages in a great work of reconstruction of self and culture using symbols from myth, fiction, history, treating ideas as beings, ornamenting mental space with options of thought. Hierarchies and rules dissolve; familiar gods recede while others rotate in to be employed as metaphors, perspectives, narratives, adornments and enrichments of the self. This is a philosophy of freedom, strength and joy, of artful thinking which expands self-concept via story, focused work, and meditation in contemplative solitude—and that, essentially, is what I endorse. I believe in repairing our damaged imaginations. Promethea for president!

Space and time exploded into being. Every moment. All at once. The explosion’s still going on. This is all part of it. We are all sparks of its ecstatic, blazing consciousness.

At one memorable juncture in the comic, the titular heroine almost gets defeated by a character called the Weeping Gorilla, who depresses her so hard that she sits down and cries from pessimism. Just in time she collects herself, focuses her will, jumps up and punches him, and that’s the one symbol to sum it all: the superheroine of imagination smacks down the lachrymose simian. Reader, what you believe about yourself may become a self-fulfilling prophesy… so prophesy something richer, maybe with colors daubed on your cheeks. Yet it doesn’t take a wizard to deck the ape. In so many ways you make your space. Stop weeping—stay awake.

A Goodnight Mosaic

It was on the unseasonably humid morning of 5 February 2025, as cockroaches were beginning to conquer my bathroom, that I was ambushed in bed by angels who pressed me flat and gently explained that I no longer had “distance.” I was 36. Only my pores could scream. My girlfriend didn’t even awaken as a lick of skin was rolled back from my left earlobe to my nose. Through this oblong gap seeped the deafening scent of heaven, which forcefully remodeled my brain into a wrinkled-glass cathedral. My perturbed soul sat up in its hole and my true body entered the spirit world.

The angels had evaporated like sparks, leaving me to find my own way in a rocky landscape. Parched, calling for help or at least enlightenment, I wandered for hours between granite crags and valleys of limestone, till at last I noticed a flickering crevice below a boulder. When I knelt down and applied my eye to the cranny, I saw a world lit by black embers. I was then granted a vision of Hell.

There is just one Hell, and it is mortal. In fact, it is dying. It is in the shape of a man, a man made of cities and roads, factories, hospitals, junkyards and cemeteries. We have all seen its silhouette. Through its mechanized, oil-barrel wastelands, three heraldic forces run rampant. Sometimes these forces compete, sometimes they cooperate, but they are always at war, continually transforming the innocent or wasting passersby who, instants before their date with history, had looked bored to death.

First were the rainbow angels. The plummet from Heaven had not changed them; while abovecloud they’d been as rigid. These authorities had ringlets of fire, eyes of ammolite, wings of peacock phoenix. In their left hands were calipers, in their right hands armillary spheres. Locked in ranks, so that ten thousand angels made one colossal angel, they could, by absorbing humans into their hive mind, marshal great legions. Their beauty was the majesty of their might, yet their god had long since absconded. They told solemn legends of his golden mask. His sad Cheshire smile.

Seeking respite from their uniform multitudes, I turned my gaze to the crack’s sky. Instead of relief, I found there a rounded blackness: a giant cauldron, towering over the moon, in which a whitebearded titan steeped his hirsute feet. At short intervals the titan, wearing a bathrobe and emitting deranged giggles, bent down and fished from his footstew the steaming, still wriggling body of a Thor or Baba Yaga, a Minerva or Santa Muerte. Lustily breaking chunks off the Trimurti, the crazed whitebeard gobbled gods nonstop, grunting with pleasure and cronking inarticulately, for he was a cretin unable to utter—a mum hunger. Meanwhile the pyre under his cauldron was kept blazing by a continuous heaping of human bodies, generation after generation consigned to immolation for his ungrateful sake.

O, horrors beyond all comprehension! Yet this revelation of the hell of man was not yet complete: a third force contended for human wills. A lost, leering, lunatic goddess. Wearing a crimson robe with a cobra for a belt, carrying a flambeau in either hand, she sprinted through the darkened world with grey visage contorted, all triangle teeth and hard skin, raving, raving. Upon hearing her mad jabber, those people with chthonic entities hidden in their DNA, with maniac devils backloaded into their subconscious, set off raving with similar verve, faces identical to hers. Her retainers were the Korybantes, an ecstatic crew of warriors; enraptured, irresistible, and precipitous, they did what their axes told them to do, chopping at the Tree of Life, making its baubles fall and explode into conceptual shrapnel.

Was there any hope? Godsatan would not budge his angelodemonic head with its horned halo and sacramental smirk, his forked feathers or his hoofs like the roofs of basilicas. Jesus, son of Eros, sighed dreambound into his heavenly mirror, the crystal lake of Avernus; his last devotees laid hands only on themselves, resurrected into new graves. Here and there not uncommonly appeared a maelstrom of pigment, a vortical flash of incarnated afflatus, feminine rumor of another world—a flametaker lighting up concrete crypts—but her messengers puttered alone in closed homes, trapped in private transcendence, gathering only to argue in grief while every splendid parrot was shot, forests turned to toilet paper, metropolises disintegrated and ripped.

Yet even as a lace of cockroaches crawls over corpses, one can become pregnant from a desire for flowers. One can stay a pervert of paradise though the breath of the lamb kills with its scent. For a moment an eye opens and bathes the sky in its light, even if that too is finally a dead man’s delight. The self is an alibi. Don’t cry. Goodnight.

P.S.: I want to write script-intensive comics, starting with short stories of 5-10 pages. Not superheroes, but still surreal or fantastical or genre pieces. And not as arcane as my fiction on here—more accessible and plotty. If you are an artist looking to collaborate, you can contact me at stefan w white at gmail dot com. I cannot pay you in anything but meticulous and entertaining scripts that may be good enough to raise your profile.

Really inspiring, beautiful piece of writing. Enjoyed it a lot!